Hermann Kappelhoff, Matthias Grotkopp, David Gaertner

1.) The Poetics of Affect in the Classic Hollywood War Film

For the investigation of aesthetic patterns and compositional strategies of emotionalization through audiovisual media, the war film genre can be regarded as a prime example because its political intention in the strategic use of audiovisual media to mobilize emotions is in most cases quite explicit and shapes the ordinary view of these films.

This intention is usually suggested by the term propaganda, meaning the influence on beliefs and convictions, but crucially also the mobilization of hostility, of feelings of collective superiority, and readiness to make existential sacrifices. In turn, the strategies of mobilizing these emotions by orchestrating audiovisual images can be systematically analyzed and described by examining the war film genre.

This set of pathos scenes is the core of our theoretical and analytical approach to the war film genre. These types of cinematic pathos have proven highly operable in our preliminary studies. In these studies, we have found out that the emotional impact of the stereotypical constellations is captured best not by one single realm of affect but rather by a spectrum or a field of tension between two poles.

This set is also derived from the premise that the poetics of affect in the classical war film is based on the staging of the relationship between the individual body and a larger military corps.

We claim that these types of narrative stereotypes and realms of affect are a useful means to make the war film genre's poetics of affect describable.

3.) An Exemplary Pathos Scene

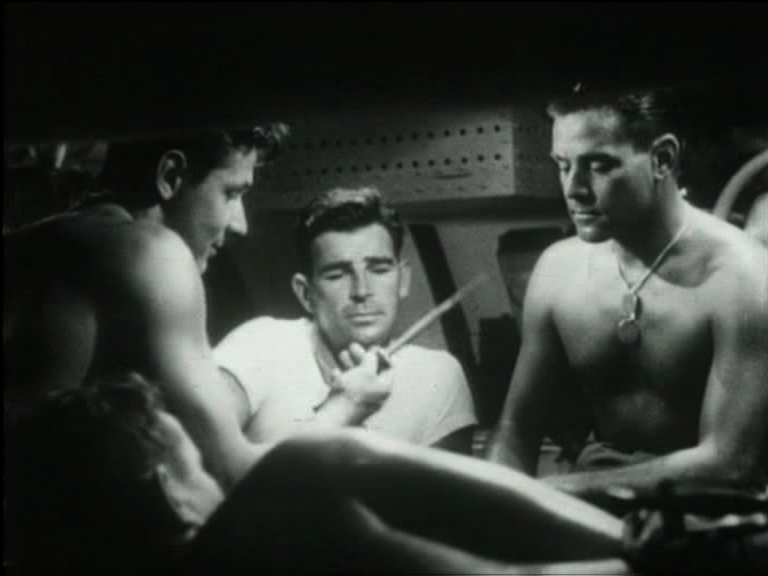

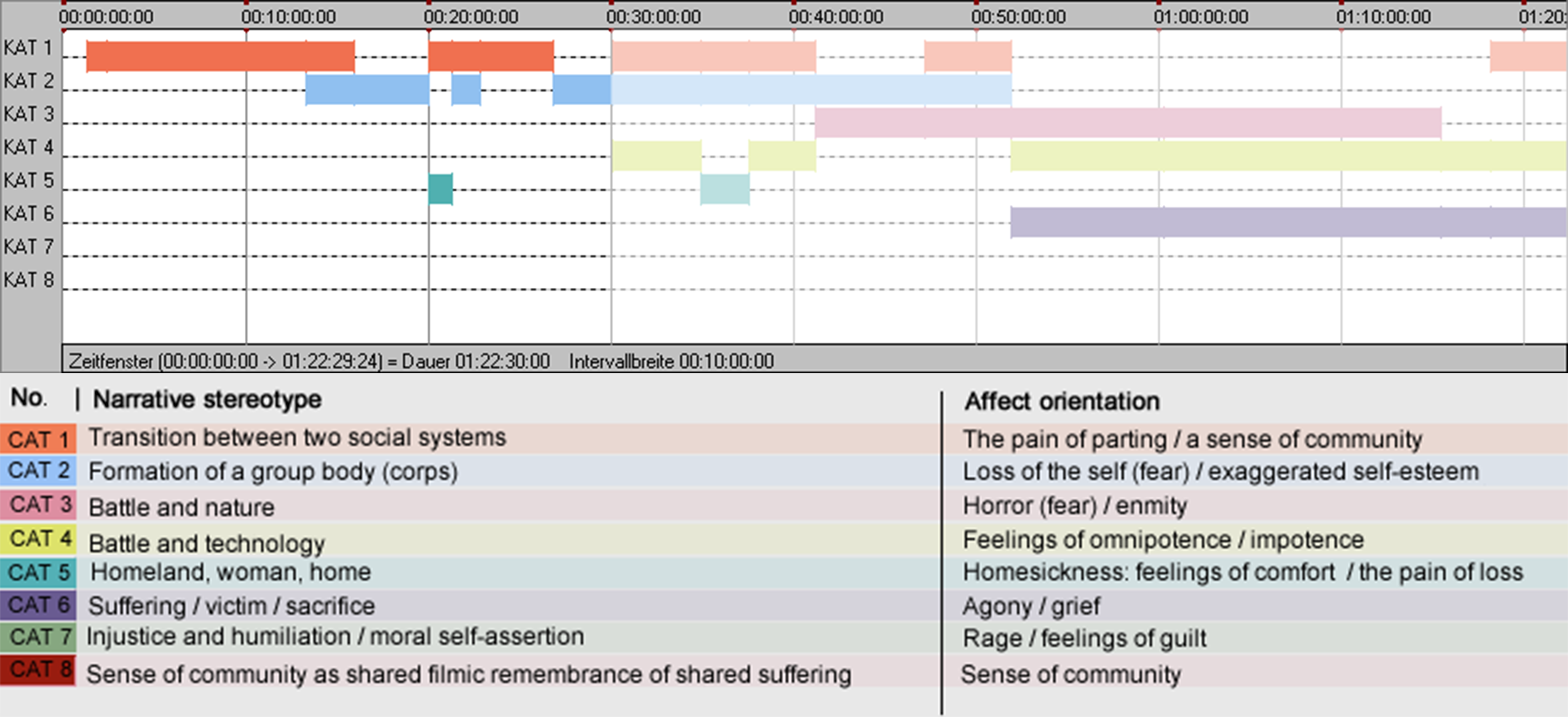

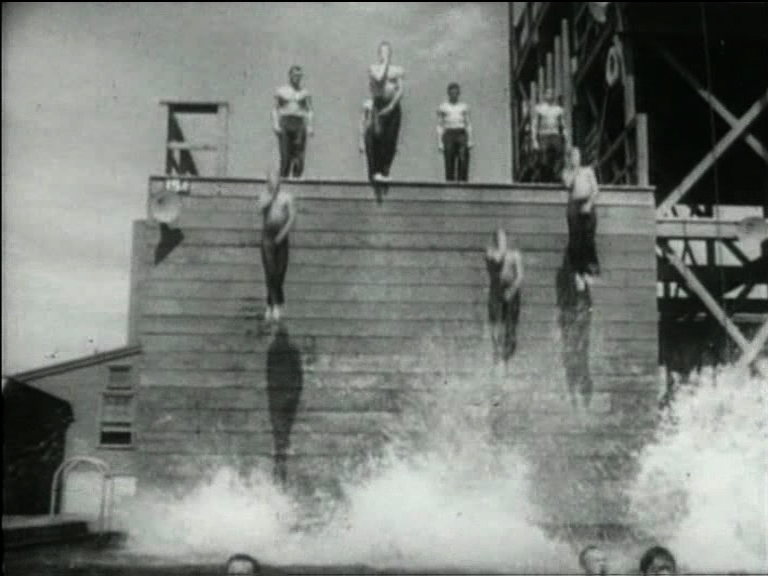

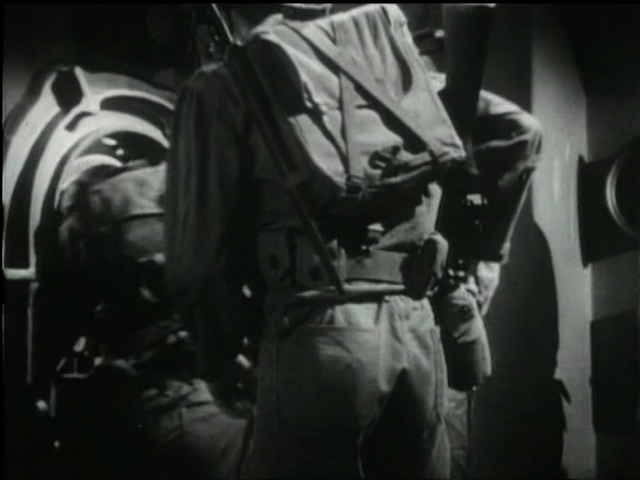

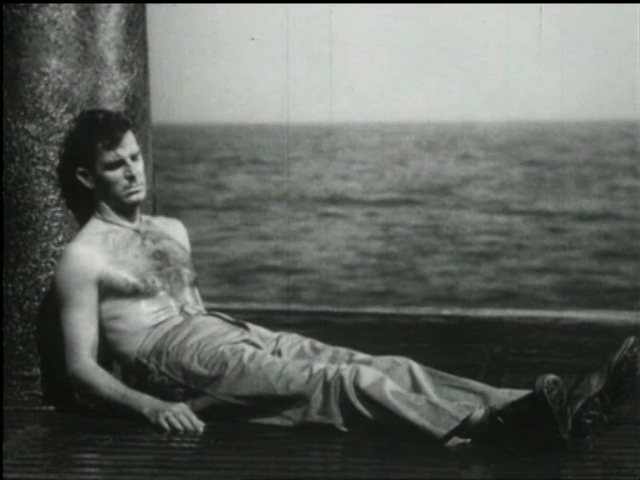

a) Individual bodies are emphasized in their concrete corporeality. They are visible only as fragments, gleaming with sweat. This staging of physical proximity is heightened by a moment of sudden fear.

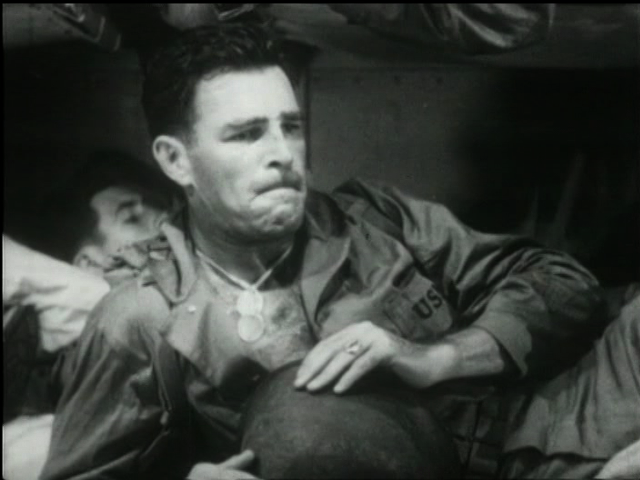

b) These fragments of bodies, however, are united in the end in a celebrating community. There is a temporal dimension that establishes this community's integrity as originating from these fragmented bodies.

c) The scene furthermore assembles this military community around one of the group's explicit father figures, qualifying it as a paternal structure. Apart from the physical confinement, the community is established as a sociality of its own, mirroring structures of civilian life.

d) Finally, the structural mirroring of civilian society is continued via a temporary return to civilian life in the mode of memory, and re-enactment. This community is gathered through an act of performing a decidedly civil ritual: the birthday party is a temporary relapse from military discipline.

Category 1: Transition between two social systems

The pain of parting / A sense of community

Category 2: Formation of a group body (corps)

Loss of ego boundaries (fear) / Exaggerated self-esteem

Category 5: Homeland / Woman / Home

Feelings of comfort and the pain of loss (homesickness)

4.) Macro-level Analysis of the Poetics of Affect

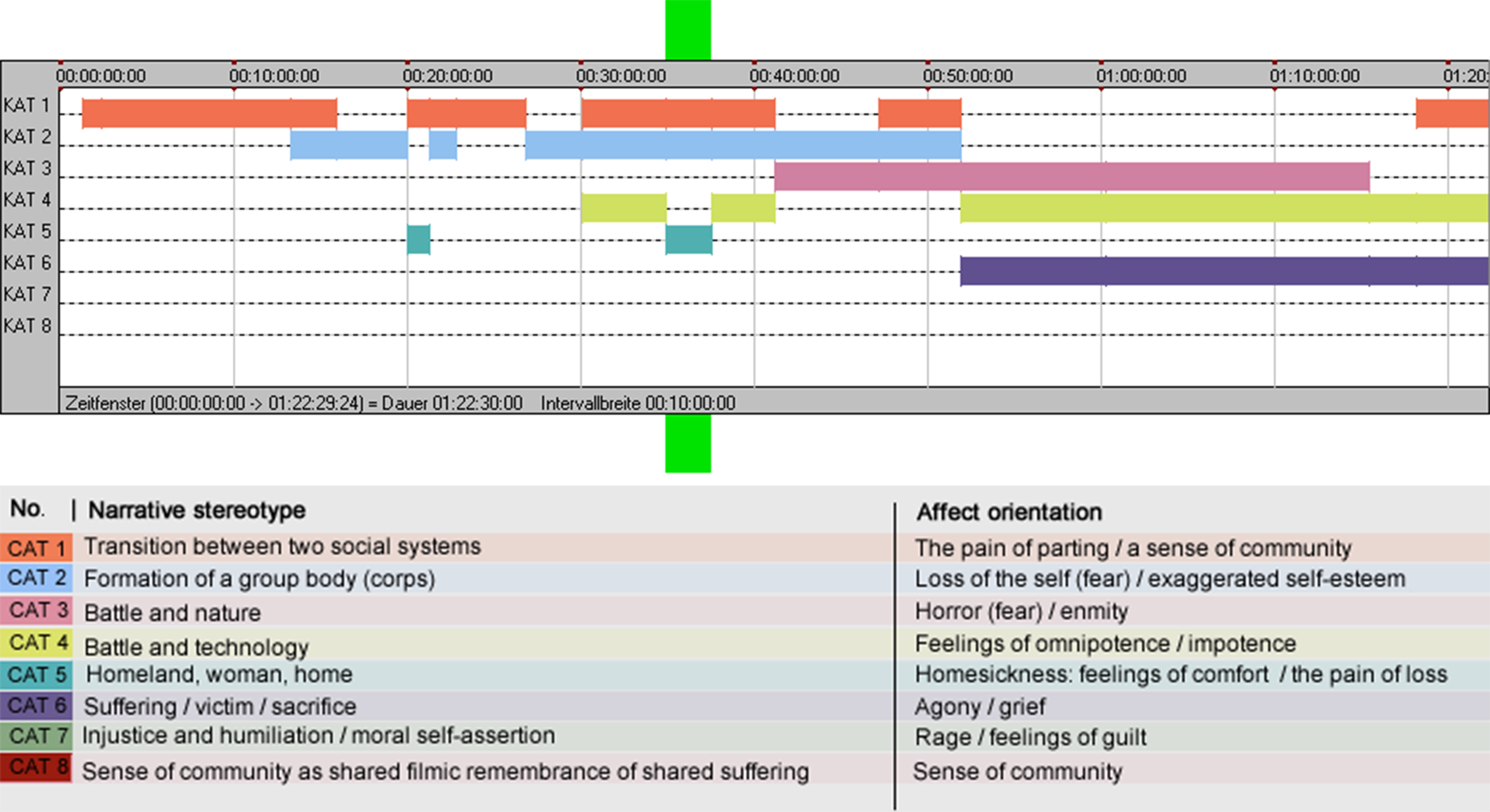

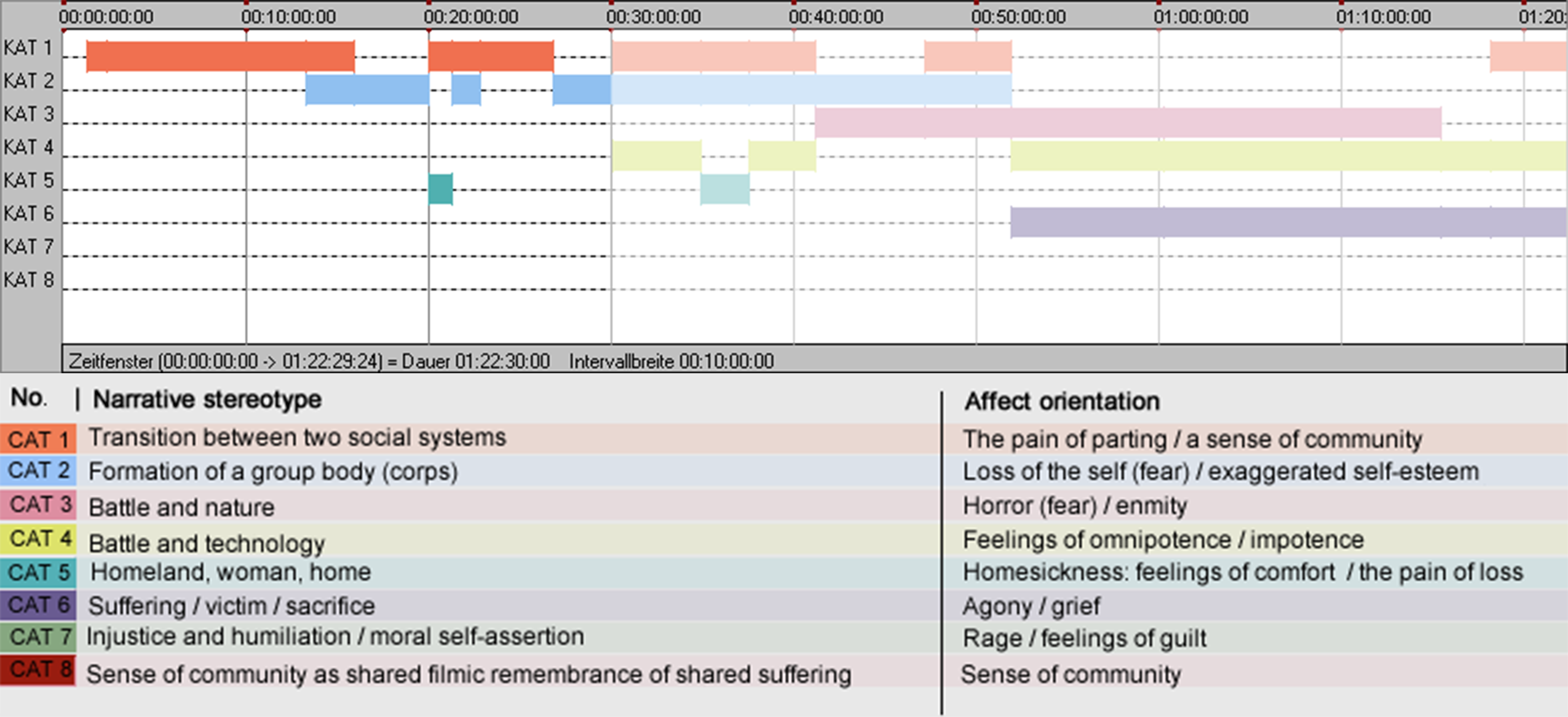

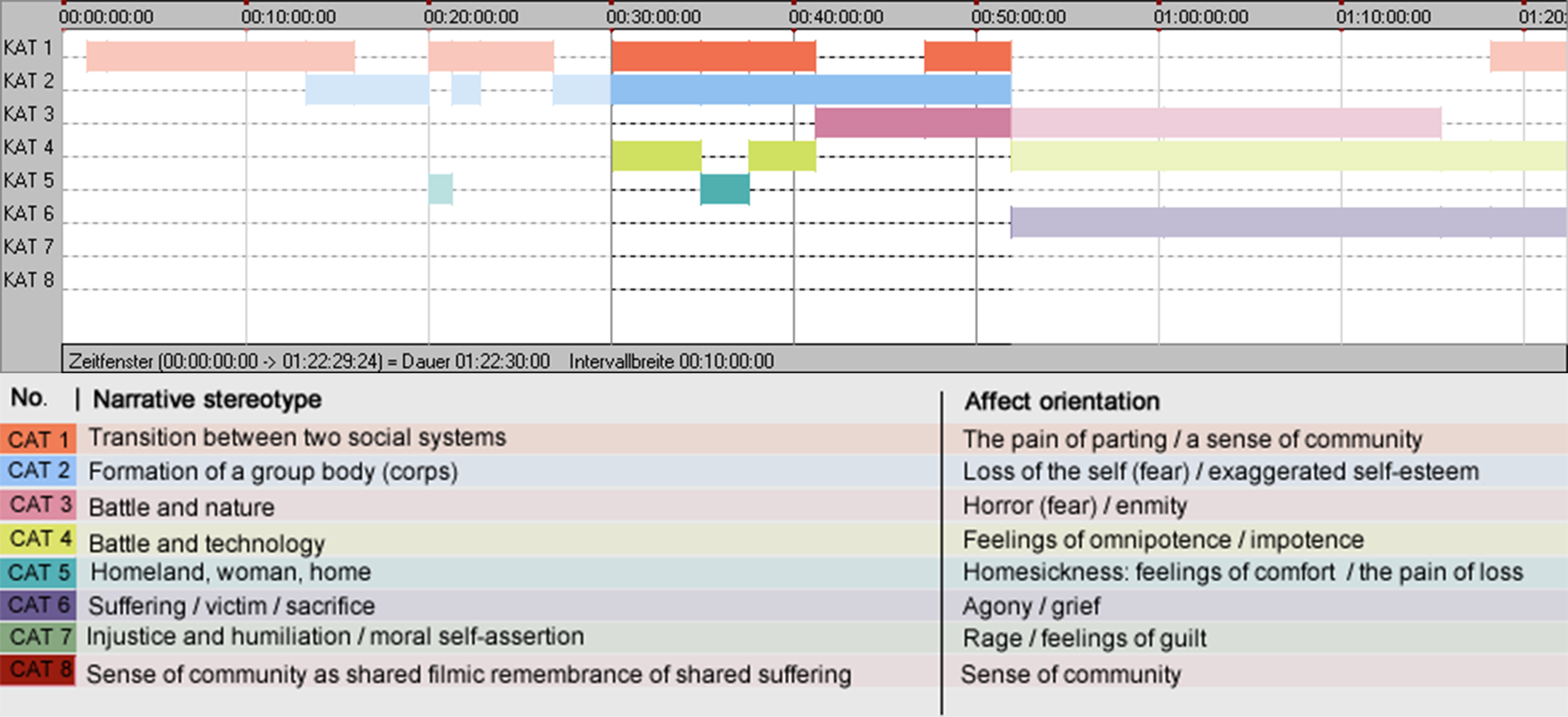

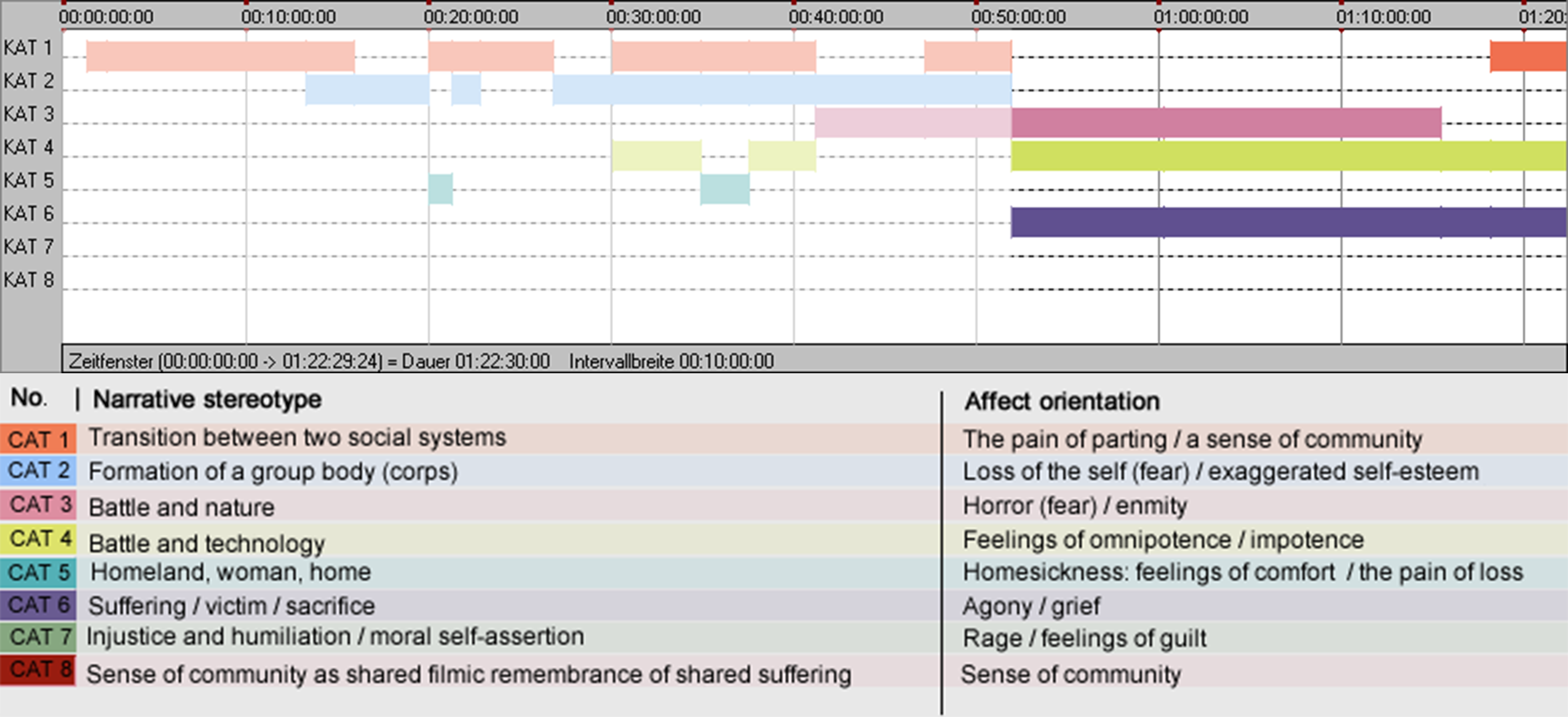

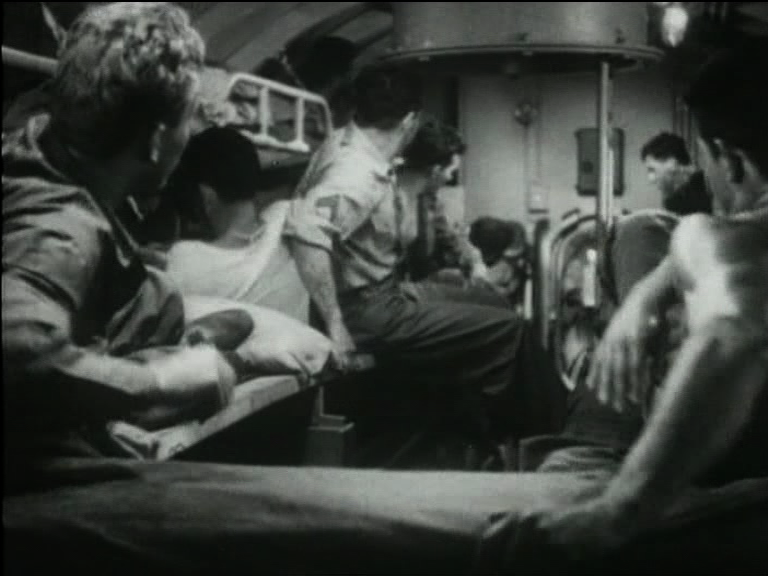

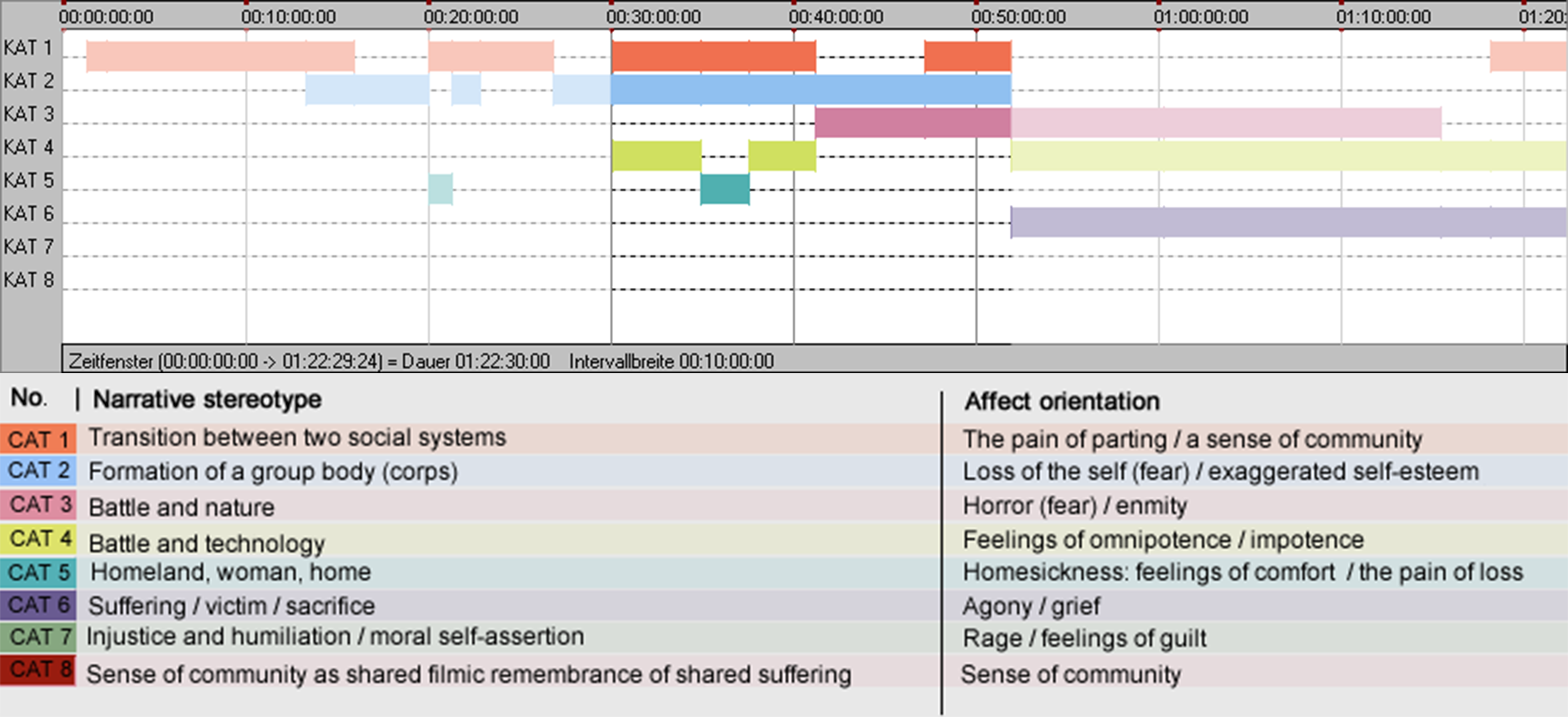

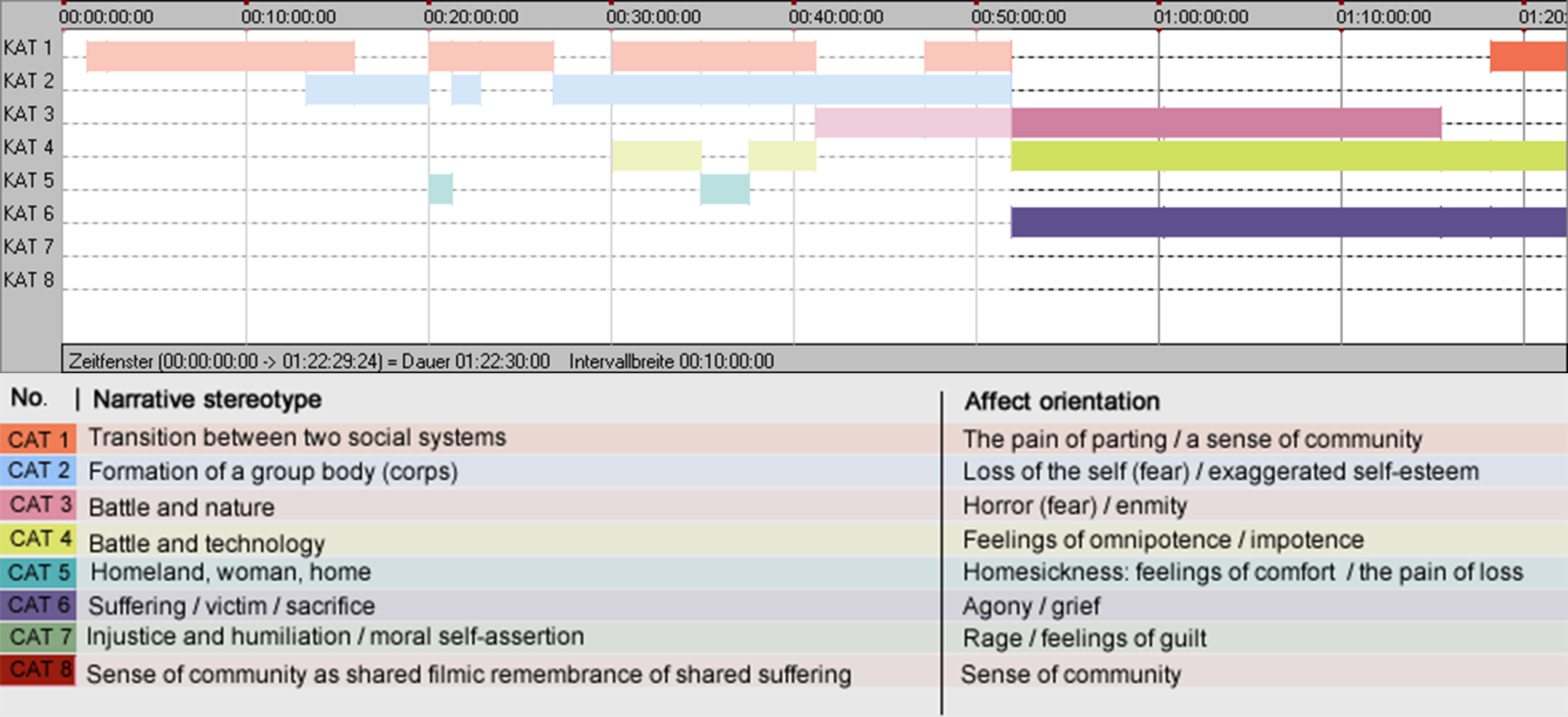

In order to visualize the structural principle and the temporal whole of the film, which the spectator traverses, we devised a simple schema to produce diagrams as transcriptions of the temporal unfolding of pathos scenes.

Each diagram represents a single film’s macro level of the poetics of affect. By comparing these diagrams we can recognize the re-occurring patterns. The degree of variance of the patterns indicates the different historical variations in the war film genre.

From left to right you see the temporal distribution of the pathos scenes over the course of the film GUNG HO! (fig. 1).

The colored boxes represent the categorical classification of scenes; each line belongs to one type of pathos scene.

The size of a scene's column is determined by the actual length of the film scene.

As you can see – marked in green –, our exemplary scene is situated at about 35 min. and is characterized as a constellation of three types of pathos scenes: Transition between two social systems, Formation of a group body (corps) and H omeland / Woman / Home.

For instance, scenes of moral injustice and scenes of filmic remembrance do not appear in GUNG HO! – so one can already clearly presume what this film is not (yet) about: the critique of military structures and the commemoration of lost lives.

What becomes evident on a first glance at the diagram of GUNG HO!, is that this arrangement makes the three-act-structure of the film clearly recognizable. It shows that we can provide an account of the way dramaturgical structures are paralleled by structures of emotional experience.

5.) Scenic Composition and Expressive Movement

The Description of a Pathos Scene's Compositional Logic

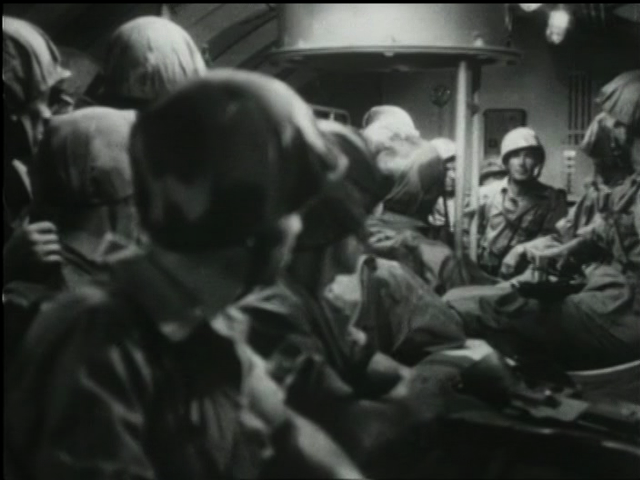

In the case of the scene "Group body in the submarine", we are dealing with a compositional logic of 'mirroring'. In the formal interplay of camera and editing, this scene superimposes the image of concentrated readiness for battle with the ambivalent echo of death. The ambivalence between the thrill of killing and the realization of one's own vulnerability is finally resolved in the family-like structure of the military community. In the film’s dramaturgical structure, this scene is between the soldiers’ arrival in the confinement of the submarine and the initiation into the collective desire to fight.

The two narrative events – the theory and practice of knife attacks and the birthday party – are correlated by a similar temporal structure and certain principles of mise-en-scène and editing. In both cases a carefully unfolded image of a distinct atmosphere is interrupted by a surprise factor from off-screen. Whereas a latent atmosphere of aggression and bellicosity is turned over into sudden fear in the first half, in the second half it is a sense of gleeful anticipation that is flipped into a moment of joyful enthusiasm. In both cases, the condition into which the elements of surprise finally stabilize is an image of conviviality and a secure and comforting sociability of male cheerfulness.

The film begins with an address that targets both the soldiers and the camera, i.e. the audience, frontally (fig. 12). In terms of image-composition, the address is situated at the intersection of nation and army, of the flag and uniformed masses. The static geometry and frontality of the shot composition formally echo the stasis and frontality of the military address. This radical frontality aligns a characteristic of the military address with the cinematic staging. It establishes the film’s relation to a reality of war and a relation to the audience – as the actor's gaze into the camera emphasizes, as he speaks the words “[...] who are prepared to kill and be killed.”

In the scenes following the drill, two aspects of the transition between two social systems are interwoven with the strengthening of this group body: On the one hand, we have motivational speeches by the team leader. On the other hand, we have scenes depicting the separation of men and women.

However, the comic dimension of this separation, caused by the numerical mismatch between one girl and two competing boys, negates any painfulness on the side of the spectator's emotion (fig. 28). Not only does this comic mode potentially affirm the process of separation. By saying 'It is all right, at least one of them will surely come back', the comic mode also comforts those who are left behind in an almost cynical way (as if it didn't matter which of them would come back).

This fear is retracted with relaxation and harmony, using humorist dialogue and calming music, in a manner similar to the scene we have analyzed in Chapter 5 (fig. 37). The transformation of physical tightness into a communal closeness is – without any exception – typical for every scene of the second act.

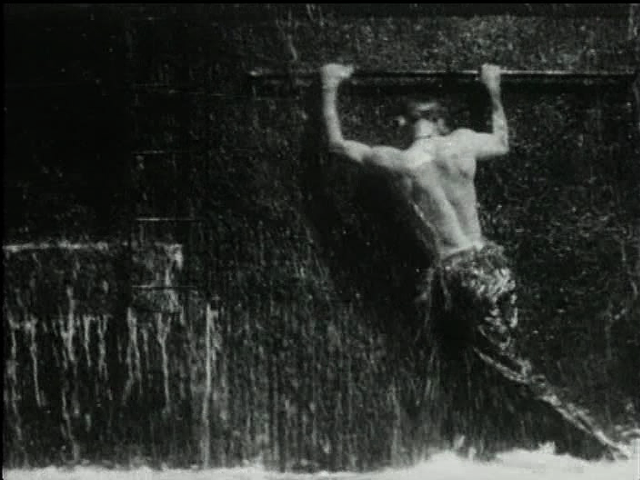

Another crucial scene in the second act concentrates again on the character who had the claustrophobic fit in the beginning (see figs. 34–36). Here, it is his exhaustion that separates him from the geometry and dynamic movement of the group. As the approach of Japanese fighter planes forces the submarine to dive, he is forgotten outside (figs. 38 & 39).

In the nick of time, and by putting the whole group at risk, this individual soldier is rescued. The geometry and the tightness of the group body are transformed from a suffocating, fearful entity into a place of security and mutual care: no man left behind (figs. 40 & 41).

Afterwards, the rhythmically complex audiovisual composition of explosions and the rocking and shaking of the submarine leads to a unification of the individual soldiers' faces as they move from being afraid, each for himself, towards laughing and feeling secure together (figs. 42–45).

All scenes of the second act create a repeated structure of escalating affective ambiguity, fear and terror, only to retract them with forced humor, calming music, demonstrative sovereignty of the superiors and images of collective harmony. This tension of escalation and neutralization is accrued through these repetitions. Cohesiveness in the sense of a physical force, holding the collective together, is thus strengthened.

Our approach provides a framework for the systematic analysis of the classic Hollywood war film genre as a poetics of affect modulating the viewer’s emotional involvement. We are also able to perform comparative investigations of the war film genre within a wider historical scope (cf. Kappelhoff et al. 2013; Kappelhoff 2016; the articles in this special issue). Experiences of history and memory are made accessible through the poetics of a genre that we described as embodied sensations elicited by the films compositional structures and generic modalities.

Films like THEY WERE EXPENDABLE (John Ford, US 1945) or SANDS OF IWO JIMA (Allan Dwan, US 1949) shape an experience of history, a shared memory of collective suffering and collective grandeur by shaping and re-arranging the war film’s forms of emotional mobilization, as a contemporary cinema audience has experienced them with films like GUNG HO! or BATAAN (Tay Garnett, US 1943). In a similar vein, we can show how shifts in the relation between the images of later wars in Vietnam or Iraq and the public sphere inscribe themselves in and are shaped by the shifts in the war film genre's poetics of affect.

The classic Hollywood war film orchestrated the images of war as an aesthetic experience between rites of initiation, sacrifice and commemoration. It brought forth pathos scenes, narrative stereotypes and audiovisual compositions charged with affective appeals. These aim at the aesthetic pleasure and embodied affectivity of the spectator and the memory of the documents of war at the same time, striving to create a palpable sensation as a sense of community (Kappelhoff 2012). This sense of community is less the content of GUNG HO!’s final address, it is rather the mode of moral, emotional and aesthetic judgments underlying the speech, underlying the poetics of affect traversed by the spectator up to this point in the film.

The political, historical and social dimension of the genre is located not in the messages, historical facts or statements but in this sensation and its reconfigurations. As progressions through the pain of parting and the triumphant merging, through fear and omnipotence, through longing and suffering, these films are part and parcel of historical, psychosocial economies of affect. Through a systematic method of genre analysis, these forms and modalities can be described as experiences of history and memory that merge and express themselves through the images of war in the Hollywood war film genre.