Hermann Kappelhoff

In the following, I would like to explain this approach by means of a case study that compares Frank Capra’s WHY WE FIGHT series (US 1942-1945) with a film of Leni Riefenstahl’s: DAY OF FREEDOM: OUR ARMED FORCES [TAG DER FREIHEIT: UNSERE WEHRMACHT] (G 1935). Leni Riefenstahl's short film was produced on the occasion of the reintroduction of the 'Allgemeine Wehrpflicht'. Just like Capra's series of films, it addresses young recruits that are yet to be initiated into the war.

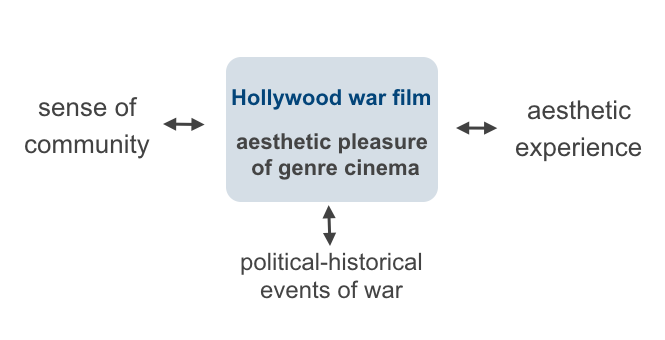

Both films unfold the ethos of belonging to the singularity of the community, both target the pathos of self-sacrifice as the pledge or precondition of this belonging. And yet it is hard to imagine a greater contrast than that between their poetic concepts!

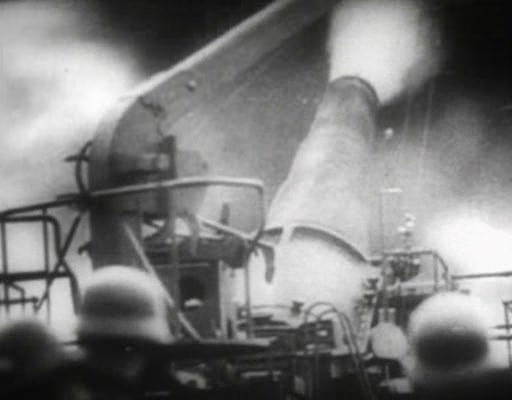

2.) DAY OF FREEDOM: Celebrating Obliteration

Through the elaborated rhetoric of dynamic montage sequences, an image of strictly methodical annihilation appears: The everyday body introduced at the beginning of the film is the object of a ritual dressing that obliterates this body.

This obliteration forms the basis for the life of the troops, the marching line, the battalion, the division, the army, and the nation.

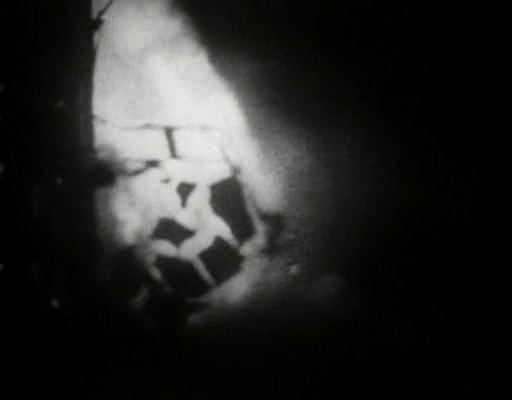

But the emotional sensation that attempts to tie the audience to these forms of community is based on a fundamental aesthetic mode of experience in the cinema: namely, the capacity to provide a dynamic element to the spectator’s space of perception and sensation, extending far beyond the scope of everyday perception. We know this mode from avantgardistic concepts of cinema: as an illusion of a gaze that, since it is rooted in the idea of the amalgamation of technology and the human body, can overcome even the most complex figurations of time and space. Here, this potential of a dissolution of perception is used to turn Hitler’s position into an aesthetic experience for the movie spectator.

From this perspective, the war itself becomes a spectacle of socialization. What is staged is the obliteration of everyday life as a solemn sensation of community, which the audience can take part in through their aesthetic pleasure.

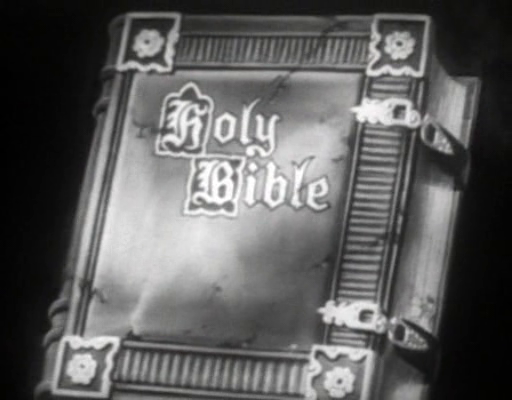

It is this ideal of community, which can be grasped in the calculated staging of the images, which leads Capra to believe that these images could be turned against their creator.

3.) WHY WE FIGHT: Celebrating Polyphony

To conclude: Capra and Riefenstahl each propagate an ideal of community, but they could not be more opposed. Riefenstahl uses the avant-garde art of montage to construct a homogenous perceptual perspective. She aims to fulfill the idea of a heroic artwork, one which would allow the spectator to take part in the staging of the power of the state. The spectator shares the Führer‘s gaze, the elevated strategic position of the commander‘s hill that turns war into a spectacle, that takes pleasure in the annihilation of the individual and the birth of an ethnic people‘s community. The film creates an audience that can enjoy the beauty of a tragedy illuminated by the aesthetics of the classical film avant-garde.

Capra, on the other hand, multiplies the perspectives and standpoints by using montage to juxtapose highly heterogeneous modes of representation. Each of these modes has a different perspective, a different affective stance to the world: the montage of association, the cross-section montage, the mode of melodrama, and that of the gangster film. This multiplication of perspectives confronts the heroic self-representation of the fascist state with the clash between opposing subjective stances and affective positionings. Capra uses the representational modes of the cinema to lay bare the ideal of community in the enemy’s propaganda films and in the same stroke to mobilize the moral judgments of his people, and thus also their sense of community. This implies the emphatic idea of political argument.

![Fig. 3: DAY OF FREEDOM: OUR ARMED FORCES [TAG DER FREIHEIT: UNSERE WEHRMACHT] (Leni Riefenstahl, G 1935).](http://medien.cedis.fu-berlin.de/loe/mediaesthetics/ausgabe_01/kappelhoff/02_cover.jpg)

![Fig. 4: Still from DAY OF FREEDOM: OUR ARMED FORCES [TAG DER FREIHEIT: UNSERE WEHRMACHT] (Leni Riefenstahl G 1935), min. 3.](http://medien.cedis.fu-berlin.de/loe/mediaesthetics/ausgabe_01/kappelhoff/04_still.png)

![Fig. 5: Still from DAY OF FREEDOM: OUR ARMED FORCES [TAG DER FREIHEIT: UNSERE WEHRMACHT] (Leni Riefenstahl G 1935), min. 3.](http://medien.cedis.fu-berlin.de/loe/mediaesthetics/ausgabe_01/kappelhoff/05_still.png)

![Fig. 12: Still from DAY OF FREEDOM: OUR ARMED FORCES [TAG DER FREIHEIT: UNSERE WEHRMACHT] (Leni Riefenstahl G 1935), min. 6.](http://medien.cedis.fu-berlin.de/loe/mediaesthetics/ausgabe_01/kappelhoff/12_still.png)