Naomi Rolef

1.) Judgment Day - The War, The Film

Introduction

The Yom Kippur War is considered one of the most traumatic events in the history of Israeli society. In many ways it was an antidote and anticlimax to the general sense of euphoria which followed Israel’s swift victory six years earlier, in the Six-Day War.

The Israeli government and its intelligence services, who were convinced of Israel’s invincibility, failed to anticipate the war. To the Israeli forces the attack on the Day of Atonement came as a complete surprise, and the military was accordingly unprepared for combat with the Egyptian and Syrian forces (1). As a result there was much chaos during mobilization and at the front. The Israeli public thus lost its trust in the political and military leadership. The war was the catalyst for civil unrest, protest movements and ultimately a change of government (Rolef 2000: 177ff.).

(1) This is a commonly accepted historical narrative, see for example Geller 2012.

The number of casualties on the Israeli side was the highest since the War of Independence in 1948 (Kumaraswamy 2000: 2), and the financial costs had long-term implications. While the Six-Day War brought economic prosperity, the Yom Kippur War resulted in a deep recession (Bruno 1986: 276f.). Although the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) had succeeded by the end of the war to overcome the Egyptian and Syrian armies, the general feeling among Israelis after the war was that of loss and defeat (Inbar 2008: 3f.).

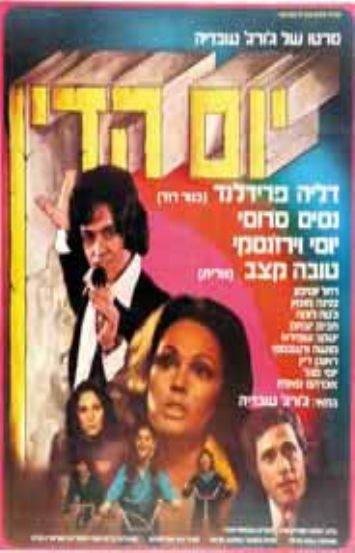

The difference between the two wars was also evident in their depiction in Israeli film. Among the films made right after the Six-Day War were several lucrative productions which featured the war and were distributed abroad as well as in Israel (cf. Shohat 1989: 103f.). In contrast, JUDGMENT DAY (YOM HADIN, Israel) from 1974, directed by George Obadiah, was one of only two films produced immediately after the War of Yom Kippur to deal with it directly (2). Just as palpable was the fact that unlike the Six-Day War films, JUDGMENT DAY was a melodrama rather than an action war film (Fig. 1).

.

(2) The other film,THREE AND ONE (Mikhail Kalik, Israel 1974), relates to the war in an implicit and symbolic manner. It ends before the war begins and the war events aren’t manifested in the imagery or plot. It would take years before additional films would address this historical event directly: THE VULTURE (Yaky Yosha, Israel 1981); THE LAST WINTER (Riki Shelach Nissimov, Israel 1983);, THE WAR AFTER (Uri Barabash, Israel 1991); KIPPUR (Amos Gitai, Israel/France 2000).

JUDGMENT DAY - A War Film?

As such, JUDGMENT DAY did not receive much attention from Israeli film scholars. Nizan Ben-Shaul failed to notice its existence when he claims that THE VULTURE (1981) was the first Israeli production to refer to the Yom Kippur War (cf. Ben-Shaul 1997: 33f.). Meir Schnitzer concluded that JUDGMENT DAY failed to go beyond the private sphere into the national one (Schnitzer 1994: 149). And Miri Talmon on the other hand only mentioned the film briefly with regards to the representation of war, with a critical remark on its patriotic overtones (Talmon 2001: 33).

At first glance it would seem that those scholars were right on the mark. The film carries the name given to the war by the defense minister, Moshe Dayan. Nevertheless, JUDGMENT DAY does not focus on the events of the war itself. It is a musical melodrama which revolves around the disintegration and reestablishment of the family unit. It follows the personal trials of the Chen family; these are manifested in betrayal, divorce, loss, grief, longing, illness and injury on the one hand, and in recuperation, artistic success and familial celebration on the other. In the plot, David, father and hotel manager, forsakes his family for the benefit of sexual exploits. This leads his wife, Shoshanna, to divorce him and sever all connections between him and his daughter, Vered. The latter suffers from the consequences. She then grows up to marry the family friend, Nissim, a nightclub singer, and becomes a singer as well. David, who moved with his girlfriend Helen to the USA after the divorce, is alerted to the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War and returns to Israel to take part in it. He is wounded and delivered to the hospital in which his daughter volunteers. Only after she saves his life with a blood donation, do they encounter and recognize each other; the family is again united.

The war erupts in the last third of the film, and the battlefield itself appears only briefly in two of the four sequences of documentary footage that are integrated into the film. And although there are dramatic moments which evoke the sense or spirit of war (Clip 1), the war could easily be read as mere pretext for a melodramatic turn of events which unites the protagonists.

Clip 1: JUDGMENT DAY (George Obadiah, Israel 1974), Min. 65-66.

However, as Shmulik Duvdevani has already observed, the war is much more integral to JUDGMENT DAY, for the film’s plot, characters and manifested emotions are compatible with public sentiments in Israel following the war (Duvdevani 2010). Furthermore, as I shall demonstrate, the Yom Kippur War is present at every level of this film. Not only in the plot and the emotional sentiments it evokes, but in its very composition, editing and supposedly anachronistic design. JUDGMENT DAY is more than a historical document that captured some of the post war’s Zeitgeist. Its melodramatic structure and features are all directed at capturing the unprecedented sway of emotions that took place in the Israeli public sphere in the war’s aftermath, and at arranging this into a composition of meaning.

2.) The Echos of War in JUDGMENT DAY

That JUDGMENT DAY is completely invested with the realities surrounding the Yom Kippur War is evident particularly in those elements of the film which appear to be flawed, namely: its abrupt editing, with sudden shifts between scenes; the misplaced comical scenes, which interrupt the film over and over again; and its historical anachronism. A closer analysis of these elements may illustrate how the war and its public implications are encompassed poetically within the film.

Editing

Much of the editing in this film draws the viewer’s attention in a negative sense, since it breaches the basic rules which would allow for its transparency, and seems to be doing so unintentionally. Some of the transitions from one image to another are conducted abruptly, creating the impression that a new scene barges onto the screen before the previous one is completed. Thus, the image of David making passionate love to a woman intrudes upon the close-up of Shoshanna’s distraught reaction to her daughter’s request to have her father attend her school performance. After Vered collapses during her school performance, the close up on her unconscious countenance, while lying in hospital, interrupts on David and Helen’s date at a nightclub. Shoshanna’s discussion with her lawyer is cut by David’s subsequent phone conversation with him. And the conflict between mother and daughter over the latter’s plans to become a singer is overtaken by her performance at the nightclub.

As these descriptions imply, the film’s editing does correspond with its narrative, accentuating oppositions and swift progression. But the true poetic motivation and affective value of this brisk editing style are revealed when put into context in the first sequence of documentary footage representing the war (Clip 2) . In this segment the editing is most sharp and unpredictable.

Clip 2: JUDGMENT DAY (George Obadiah, Israel 1974), Min. 62-64.

The sequence interrupts an emotional scene in which Shoshanna is confronted by her parents for having no spouse, and is abruptly put to an end by David’s reaction to the tidings of the war. This second rapid shift is intensified by the fact that it marks David’s unanticipated return to the narrative, which followed Shoshana and Vered after his departure. The swift transition to and from the documentary footage enables the audio-visual presence of war to appear suddenly, ‘out of the blue’, and reenact for the viewer the shock of an unexpected attack so central to the experience of the Yom Kippur War in Israel. This effect is enhanced by the arrangement of the documentary footage, in which all sense of coherence is delayed for a short spell. It is the sound of an Israeli fighter aircraft which intrudes on Shoshanna’s words. Footage of aircraft taking off merges with the sound of sirens accompanying the sight of Israeli civilians running through the streets. Only after this initial footage are the Egyptian forces shown marching into Israeli territory. They are followed by the audial fragments of a radio announcement and the sight of Israeli civilians gathering around transistors. After this elucidating segment, a presentation of the various fighting forces ensues. This short sequence reconstructs an individual consciousness confronted by events and alerted by their immediacy before it eventually creates an intelligible narrative.

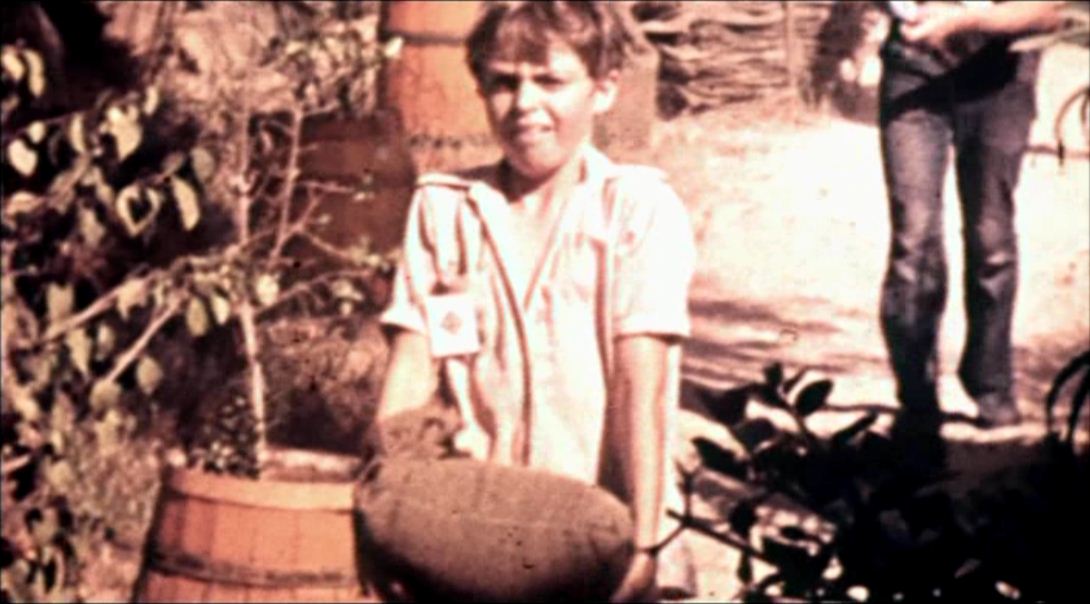

The ending of this scene is just as evocative. The documentary segment is cut short by a close-up of David. This disrupts the music that accompanies footage of youth and children mobilized for the war effort. Here a gap is created between these youths (Fig. 2) and David (Fig. 3), between their mobilization on the home front and his static posture in a mise-en-scène which communicates wealth and comfort. This oppositional representation underlines the rapid change of perspective prompted by the war. David’s previous conduct loses its final justification in the face of the national state of emergency. This abrupt transition from one image to the next is the sole visible catalyst for David’s swift transformation into a mobilized citizen, a self-sacrificing soldier and a dedicated family man.

...in contrast to David's lack of mobility

The second sequence of documentary footage depicting war begins and ends just as suddenly as the first (Clip 3). Its integration into the film is, however, less disharmonious. The beginning receives an ironic twist, when integrated into a comic scene, which I shall refer to bellow. It is coordinated with the movement on the screen, a drafting officer waves his hands impatiently and calls “Army, army, army, enough!”, bringing on a set of images from the battlefield. Its ending provides an example of invisible editing, as the movement of the stretchers in the last documentary image, from left to right, is continued in the next sequence, which takes place in the hospital. Here a different style of editing is employed to merge the historical event in the documentary footage with the fictional events in the narrative.

Clip 3: JUDGMENT DAY (George Obadiah, Israel 1974), Min. 69-70.

Comedy

The role of comedy in JUDGMENT DAY is similar to that of the editing. It appears flawed at first, and becomes intelligible within the context of war. The comic scenes in the film, which appear at different stages, are based on a variety of ethnically marked comical figures. All figures function in a similar manner with the exception of the most prominent ones among them, Shoshanna’s parents. Most comical figures appear only once in the film, and through their comedy acts disrupt its progression. A droll cleaning man stops Shoshanna in the hotel lobby before she walks in on her husband and his mistress. Shoshanna’s meeting with the divorce lawyer is likewise delayed by a display of a physically dysfunctional couple in the waiting room. At the airport, David’s military recruitment is stalled by a small Yiddish-speaking man who demands to be drafted (Clip 4). And in the hospital, it is a slow outlandish laboratory manager who declares that there are no more fresh blood units for the fatally wounded David. One would expect those humorous figures to bring comic relief, but instead their effect is rather the opposite. Their performance interferes with the flow of events, and in most cases one of the main characters is depicted waiting impatiently for it to end. Their appearance is untimely and misplaced, given the wrong context and settings, creating irritation rather than alleviation.

Clip 4: JUDGMENT DAY (George Obadiah, Israel 1974), Min. 67-69.

But this apparent faulty use of comedy serves a purpose. Its poetic impact becomes clear when the war enters the film. While the abrupt editing echoes the sudden eruption of war, the misplaced comedy scenes illustrate in a most poignant manner the sense of inadequacy shared by the Israeli public in facing the state of emergency. The comic irritation caused by temporal delay and inappropriate conduct has no motive when introduced before the war. Its deep-seated effects become comprehensible after a state of emergency is introduced, and its occurrence hampers military mobilization and medical urgency. It mirrors some of the systematic disorder and irregularities which sabotaged the war effort and were publically denounced after the war. It is significant that the laboratory scene is concluded differently than the other, comical scenes. Vered responds and takes action, volunteering to donate her blood, which is the type required, and thus revokes the irritation (Clip 5). This is not only a demonstration of self-sacrifice, but also of resourcefulness. It corresponds with an experience attributed to the Yom Kippur War, according to which, in the face of organizational dysfunction, much was achieved through the creative efforts of individual recruits. Or in other words: “[…] the outcome of the war reflected far more credit on the reservists as individuals than on the framework of which they formed a part.” (Cohen 2000: 96) The following scene of Vered’s blood donation is laden with perceptible pathos, confirming the valor of such individual initiative.

Clip 5: JUDGMENT DAY (George Obadiah, Israel 1974), Min. 70-72.

Anachronism

The third ostensible flaw in the film, namely historical anachronism, functions on a different perceptual level than the other two. It’s created through the discrepancy between the length of time covered by the plot and the historical landscapes as they are presented. The film’s plot follows Vered Chen as she grows up and marries – an undefined period that would in any case be longer than six years. However, since the central settings in which the film takes place all reflect the development which came about in the period between the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War, their full effects depend on the viewer recognizing the scenery:

Ramat Aviv in Tel Aviv, where the film begins and where the family lives, was subjected after the Six-Day War to several development projects, consequently becoming the wealthy neighborhood seen in the film, a lasting symbol of the new middle class (Fig. 4-6);

Jerusalem, where Shoshanna’s parents live, is represented almost exclusively by locations previously lying on the borderline of the divided city (Shlomzion Street, Yemin Moshe, the train station). Moreover, the camera concludes the depiction of Yemin Moshe with a lingering view of the Old City, which was once outside Israel’s domain. The unification of Jerusalem that took place in the aftermath of the Six-Day War is thus visually underscored. Unlike the portrayal of Ramat Aviv, the change is not indicated by a wholly new cityscape, but by the sight of what previously existed under much different circumstances (Fig. 7-9);

Eilat, where David and Helen fall in love, had similarly changed its status after the Six-Day War. Once a peripheral border town, it became after the occupation of the Sinai Peninsula its central gateway. The newly established northern promenade is portrayed in the film (Fig. 10);

and Sinai in turn appears not only as part of the romantic scenery in the sequence about David and Helen’s vacation, but also as a marked military zone, where Nissim is posted for reserve duties and where David is ultimately wounded in battle (Fig. 11-13).

In other words, the scenery is not used to support any kind of temporal credibility. Instead, it is recurrently marked as a contemporary environment – contemporary to the time the film was shot and modified by recent changes. The film’s settings are thus not subjugated to the narrative. They are, on the contrary, instrumental in situating the film in the historical present and subsequently in proximity to both the achievements of the Six-Day War and the losses of the Yom Kippur War. To that extent, the time it would logically take Vered to reach adulthood is irrelevant. Her maturity process is in itself significant and directly related to contemporary events. This principle becomes more tangible through the anachronism that is generated in that process.

Through the three elements, editing, comedy and anachronism I have demonstrated how the Yom Kippur war is integrated into the very grain of the film experience. They correspond with the war on an affective level. Turning now to the narrative structure and use of genre, I shall show how the war is not only reflected in the film but is also subjected to a process which integrates it into an affirmative structure of meaning.

3.) The World in which the War Erupts

An Alarming Perspective

The proximity of the Yom Kippur War is most apparent in the scene in which Nissim performs for the soldiers in Sinai (Clip 6). This scene follows the sequence in which David and Helen are romancing in Eilat, and begins right after David proclaims himself a liberated man free to follow Helen to the USA. The sight of the soldiers and the opening musical score, which is reminiscent of military marches, appear at first to suggest a contrast to the couple’s pleasurable vacation and David’s lack of commitment to his homeland. But the scene is not one of mobilization. As the song progresses it becomes clear that its humorous theme is the idleness and leisure of the soldiers. The documentary footage depicts them not only in training, but also at rest. Nissim concludes his performance and climbs into a jeep. As he repeats a verse from the song while driving, a landmine explodes beneath him and ends the scene. The explosion has no function in the narrative and no outcomes. Its sole aim is to transform amusement to alarm, to express the lack of preparation among the Israeli forces on the eve of the war, and it also underscores, particularly in the hindsight of those who experienced the war, a premonition of the coming strike.

Clip 6: JUDGMENT DAY (George Obadiah, Israel 1974), Min. 28-32.

The Melodrama and the War

But the war is not only present in those parts of the film in which the military is portrayed. The realities of the Yom Kippur War are just as central for the melodramatic events which comprise the larger portion of the film. Here they appear in implicit rather than explicit form. By way of emotional gesture, the familial crisis in the film relates to the national one, and its main conflicts transcend the private sphere, clearly extending to the public one.

Duvdevani suggests that David’s hedonism and the lack of responsibility shown by him toward his family in the first part of the film mirror the euphoric atmosphere in Israel after the Six-Day War, and that his injury marks disillusionment as well as trauma (Duvdevani 2010). One could also recognize the echoes of national affairs in Shoshanna’s attempt to conceal all information about the divorce and David’s whereabouts from her daughter. It is reminiscent of the public outrage in the war’s aftermath over the self-censorship practiced by the Israeli media before the war, and over false information released to the public by the political leadership during the campaign (cf. Rolef 2000: 178). These parallels do not relate to the war predominantly in an allegorical form, but through the emotional weight which they carry (3).

(3) Cf. Kappelhoff on sentimental literature (2004: 238ff.).

Melodrama as defined by Linda Williams is one of the “gross” or body genres. It is “[…] marked by ‘lapses’ in realism, by ‘excesses’ of spectacle and displays of primal, even infantile emotions […]” in which “[…] the body of the spectator is caught up in an almost involuntary mimicry of the emotions and sensations of the body on the screen.” (Williams 1991: 2ff.) According to Hermann Kappelhoff, it is an enactment of the inner forces in a process most akin to modern conceptions in psychology (Kappelhoff 2004: 37f.). JUDGMENT DAY as a melodrama offers the viewers an intense emotional and sensual experience, structured within the terms of psychodynamics. When viewers encounter the war in the last third of the film, their cinematic experience of it is integrated into and defined by the emotional process they have already undergone.

Most central is the fact that the experience that the film structures is not that of trauma – as might have been expected – but of growth. Whilst a contemporary film could end with the loss of the father figure (4), in JUDGMENT DAY the father departs and is mourned for in the first half of the film, and the consequent healing process takes place before he returns. In the course of further developments, the melodrama merges with other genres which influence the emotional process through which the viewers are lead.

(4) As THREE AND ONE indeed does.

The film commences with an extreme rupture between the spaces that Vered and David occupy, with Shoshana serving as the go-between. The imagery and music which accompany Vered are typical of children genres (Fig. 14-15). The opening scene, in which she rides a bike, has all the elements of a traffic education film. And in the following scene she appears in the context of a school performance.

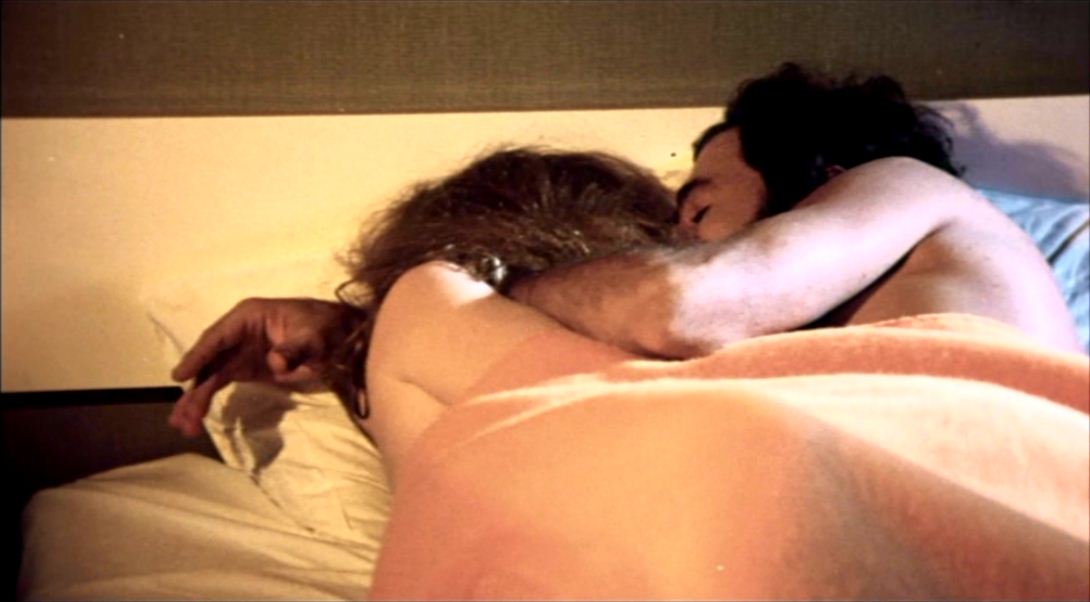

This is incompatible with the richly designed space and music, in which David’s sexual adventures take place (Fig. 16-18).

At the height of the crisis, when Vered discovers that her parents are separated, she wanders through Tel Aviv at night – in the very space previously occupied by her father (Fig. 19).

As an adult she overtakes that space. She pairs off with Nissim, her father’s companion; performs in the night club; and lies with her husband in the same position that her father had taken with his lover (Fig. 20 & 21).

In doing so, she introduces to the very same space a type of adulthood different than her father’s. While David’s visit to the club is glaringly distinguished by insignias of sexuality (Clip 7), Vered’s performance there is almost completely devoid of such markings (Clip 8). Her song articulates a rather spiritual search.

Clip 7: JUDGMENT DAY (George Obadiah, Israel 1974), Min. 10-14.

Clip 8: JUDGMENT DAY (George Obadiah, Israel 1974), Min. 54-56.

The change-over is completed in the hospital, after the war begins. While David was absent from his daughter’s bedside, Vered, as the new responsible adult, becomes a self-sacrificing nurse, consequently saving David’s life and reuniting him with the family. But the main part of the healing process in the film evolves through a gradual change in genre modus.

The familial crisis during David’s and Shoshana’s divorce introduces at first a greater spacial rupture than the one which has existed before, when all members of the family leave Tel Aviv. David goes on vacation with Helen to Eilat, while Shoshana takes her daughter to her parent’s house in Jerusalem. The move to the parents’ house brings with it visual indications of economic decline – it is no longer the luxurious environment of Ramat Aviv. As mentioned above, the parent’s house is situated on the old border, and marks the unification of the city. However, Shoshana’s parents, elderly and religious, are typical of Yemin Moshe’s population before its development in the aftermath of the city’s unification. The choice not to reflect the recent process of gentrification in this area is of symbolic value. It facilitates the association of the impoverishment which is caused by divorce with a return to a humble past. What makes this change of scenery positive is the appearance of Shoshana’s parents and through them the introduction of comedy. While other comical figures appear only shortly, disrupt progression and create irritation, the parents and their comical performance are an integral part of the events. Within this context, unlike the other figures, their comedy does generate relief. The melodramatic tone is not obliterated, but the comic intervals introduce a different perception, a lighter one.

Later, halfway through the film, the musical genre becomes dominant, ushered in by the developing liaison between Vered and Nissim. The musical scenes follow each other closely and form a succession. It begins when Nissim consoles Vered with music, and continues as he becomes her mentor. The following scenes depict Vered’s success as a performer and the couple’s marriage, which are standard themes in the musical genre. The atmosphere is elevated accordingly for the conclusion of this part through a festive family gathering before the Yom Kippur fast.

The war is therefore launched after the familial crisis has been resolved, the adult space overtaken by dignity, and familial unity and bliss reinstalled despite the father’s absence. It is a world that has survived turmoil and is almost rectified. Within it the viewers may accept, wish and even expect that the war will be met with communal strength capable of enduring the destruction. Thus, the experience of the Yom Kippur War is, within a constructive process, embedded in the film. This could be seen as the earliest indicator of a social phenomenon examined by anthropologist Edna Lomsky-Feder some twenty years later. Lomsky-Feder arrived at the conclusion that the individual experience of the Yom Kippur War had transpired not only through shock and trauma, but also as a cause of an essential maturing process (Lomsky-Feder 1996: 265ff.). One should nevertheless not lose sight of the fact that the choice to depict the Yom Kippur War as part of a meaningful process – while it was still painfully present in the public sphere – was incontestably political. And the political overtone is present as the film ends with an ultimate fusion between the nation, David’s body and the family (Clip 9).

Clip 9: JUDGMENT DAY (George Obadiah, Israel 1974), Min. 80-83.

The last sequence begins when David is rushed to surgery and Shoshanna, Vered and Nissim are left behind; the musical score commences and the scenery changes to areal footage of Sinai in the aftermath of war, dotted with scorched tanks. A soldier wrapped in prayer shawl in the desert is seen before the scenery changes to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, to prayers at the Wailing Wall, and to the image of Jesus kneeling on the façade of the Church of all Nations. The family, including a lamed but recovered David, is then seen exiting the hospital and entering a car. David takes Shoshanna’s hand and they embrace. The song heard throughout this scene is sung from a personal perspective and tells of the gates of heaven, which open for the prayers of soldiers on the Day of Atonement. The family’s initial expressions of anxious concern correspond with the various images and prayer. But more importantly, David’s recuperation – which may be read as a resurrection – is made visible through the transition in landscape. Sinai, the southern periphery, desolate, pale and burned, is not only the area in which David was wounded. It is a visual manifestation of his injured body. The shift to Jerusalem is not only a shift to the center of Israel and the traditional object of prayer. Its structured and flourishing landscape contradicts the desolation of the desert, and implies physical recuperation. It is finally complemented by David’s reappearance on the screen and the enacted reunification of the couple and the family.

The choice of scenery in Jerusalem is not coincidental. It features the Old City and its surroundings, which are significant to the three religions, Islam, Judaism and Christianity, all represented in the sequence. More importantly, it is terrain occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War campaign – and its most significant achievement at that. The symbol of victory from the previous campaign is thus being put at the forefront, where it signifies not so much remedy to the painful sense of loss at the sight of burned tanks, but rather completion, as a visual reminder of what has been preserved. It serves as the manifestation of what Abraham Rabinovich concluded – with no less pathos – some thirty years later: “Israel would bear its scars[,] but it would be sustained by the memory of how, in its darkest hour, its young men mounted the nation’s crumbling ramparts and held.” (Rabinovich 2004: 515)

Bibliography

Ben-Shaul, Nitzan S. (1997) Mythical Expressions of Siege in Israeli Film. Lewiston/Queenston/Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Bruno, Michael (1986) 'External Shocks and Domestic Response: Macroeconomic Performance 1965-1982'. In: Ben-Porath, Yoram (ed.) The Israeli Economy: Maturing through Crises. Cambridge, Massachusetts/London: Harvard University Press, 276-301.

Cohen, Stuart A. (2000) 'Operational Limitations of Reserve Forces: The Lessons of the 1973 War'. In: Kumaraswamy, P. R. (ed.) Revisiting the Yom Kippur War. London/Portland: Frank Cass Publishers, 70-103.

Duvdevani, Shmulik (2010) 'The Melodrama of the War', Ynet Film Magazine [Online]. Available: http://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-3955148,00.html [Accessed 27.12.2012].

Geller, Doron (2012) 'Israeli Intelligence and the Yom Kippur War', Jewish Virtual Library [Online]. Available: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/intel73.html [Accessed 03.01.2013].

Inbar, Efraim (2008) 'Israel Strategic Thinking After 1973'. In: Inbar, Efraim (ed.) Israel’s National Security: Issues and Challenges Since the Yom Kippur War. London/New York: Routledge, 3-23.

Kappelhoff, Hermann (2004) Matrix der Gefühle: Das Kino, das Melodrama und das Theater der Empfindsamkeit. Berlin: Vorwerk 8.

Kumaraswamy, P. R. (2000) 'Revisiting the Yom Kippur War: Introduction'. In: Kumaraswamy, P.R. (ed.) Revisiting the Yom Kippur War. London/Portland: Frank Cass Publishers, 1-10.

Lomsky-Feder, Edna (1996) 'Youth in the Shadow of War, War in the Light of Youth: Life Stories of Israeli Veterans'. In: Hamilton, Stephan F. & Hurrelman, Klaus (eds.) Social Problems and Social Contexts in Adolescence. New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 253-268.

Rabinovich, Abraham (2004) The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East. New York: Schocken Book.

Rolef, Susan Hattis (2000) 'The Domestic Fallout of the Yom Kippur War'. In: Kumaraswamy, P. R. (ed.) Revisiting the Yom Kippur War. London/Portland: Frank Cass Publishers, 177-194.

Schnitzer, Meir (1994) Israeli Cinema: Facts, Plot, Directors, Opinions. Tel Aviv: Kinneret Publishing House.

Shohat, Ella (1989) Israeli Cinema: East West and the Politics of Representation. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Talmon, Miri (2001) Israeli Garffiti: Nostalgia, Groups, and Collective Identity in Israeli Cinema. Haifa/Tel Aviv: University of Haifa Press/Open University Press.

Williams, Linda (1991) 'Film Bodies: Gender, Genre and Excess', Film Quarterly, 44, 2-13.

Filmography

JUDGMENT DAY (YOM HADIN). ISR 1974. Directed by: Obadiah, George. DVD: United King Films LTD 2008.

KIPPUR. ISR/FRA 2000. Directed by: Gitai, Amos.

THE LAST WINTER. ISR 1983. Directed by: Nissimov, Riki Shelach.

THE VULTURE. ISR 1981. Directed by: Yosha, Yaky.

THE WAR AFTER. ISR 1991. Directed by: Barabash, Uri.

THREE AND ONE. ISR 1974. Directed by: Kalik, Mikhail.