David Gaertner

In this paper I will outline an approach to genre cinema that is the basis of the work in the research project with the title “Staging images of war as a mediated experience of community” that ran from 2011 to 2016 at Freie Universität Berlin (1). On these grounds I aim to demonstrate the dynamics between genre cinema and war coverage within the institutional practice of the staple program with the example of images of casualties. In terms of the audiovisual material examined, my focus will be on newsreels that where screened together with fictional war films in american theaters from 1942 to 1945. The central concern of this study is the question of genre cinema in terms of an aesthetic experience that also accounts for a shared experience. To consolidate the historical scope of this study it will be necessary to establish an understanding of how to conceptualize the aesthetic experience of film reception within the specific realm of the staple program as a cultural and social practice. Drawing on existing concepts of the nexus of cinema and public sphere as well as on a phenomenological theory of spectator engagement I will introduce a specific definition of the term moviegoing experience. This shall help bring the two components together: the historiographical account of an institutional practice and the theoretical conceptualization of the viewer within an unique understanding of genre cinema. Thus an aesthetic practice can be described within a specific historical framework that constituted the emotional mobilization of the american public during World War II.

(1) The theoretical and analytical work presented here was pursued in the project “The mobilization of emotions in war films” at the Cluster of Excellence “Languages of Emotion” at Freie Universität Berlin. This research perspective was developed further concerning questions of intermediality and historicity in the DFG funded research project “Staging images of war as a mediated experience of community” also located at Freie Universität Berlin. I was a research associate in both projects.

The Circulation of Images and a Shared Experience

The afore mentioned project takes for granted that genre cinema plays a pivotal role in the shaping of a coherent picture of war, that emerges from an abundance of war images. These images also include war coverage, as far as it is based on audiovisual media. Between 1942 and 1945 this idea of a circulation of war image seems natural considering the fact that a variety of documentary formats were regularly combined with the showing of feature films in commercial cinemas in the United States as part of so-called staple programs. To maintain the idea of the circulation of images of war within this context it is necessary to disregard the distinction drawn between documentary and fiction film, this is the distinction between coverage and narrative storytelling. This means neglecting the notion of a rational factuality on the one side and an emotionally charged fiction on the other side.

Obviously this is not a new idea. But still, it is essential to have this thought in mind, when it comes to the question of the relationship between Hollywood films and a certain practice of screening documentary formats.

In our project, we assume that the film’s aesthetic expressions can be described as an address of the audience in a way, that they qualify as an emotional mobilization. This takes place within the framework of genre cinema understood as a system of shaping, addressing and differentiating emotional experiences. Under these auspices the spectator is situated within a shared world of sentiment, a sense of belonging to a common world of aesthetic, emotional, and moral judgment (2).

From this standpoint genre cinema can be understood as a sophisticated communication system by which a society assures itself of a consistency of shared experiences, a shared horizon of values, of world relations and social affiliations.

(2) This relates to the idea of sense of community as a topos of political philosophy developed in Hannah Arendt’s re-reading of the Kantian sensus communis (Arendt 1982) and also to Richard Rorty’s notion of commonality and solidarity as a sentimental development of moral identities (Rorty 1998) as well as the Cavellian claim to community as a mode of declaring the common under the sign of skepticism (Cavell 2004 and Norris 2006). The impact of Arendt’s thinking in relation to genre cinema is explored in a study by Hermann Kappelhoff (Kappelhoff 2009) that inquires the different conceptions of propaganda in Capra’s Why We Fight-Series (USA 1942-1945) and a short film by Leni Riefenstahl (TAG DER FREIHEIT. UNSERE WEHRMACHT, D 1935).

This experience of community, one might say, is not to be located on the level of facts presented or a narrative being told. Rather, it structures the individual views and emotional attitudes towards the moral and political issues represented (3). We assume that genre cinema is constitutive for affect-defined modalities, that concur with different types of genres but are not exclusive to each other. To consolidate this approach, I will refer to Christine Gledhills paper “Rethinking Genre” that was published in 2000. Against the backdrop of the melodrama Gledhill proposes a genre-system that is constituted by economic mechanisms, aesthetic practices and a “cultural-critical discursivity” (Gledhill 2000: 223). The film genres modalities can be understood – in Gledhills terms – as “a culturally conditioned mode of perception and aesthetic articulation” (ibid.: 227). The modalities transcend mere narrative subjects and can be described along historical lines:

(3) This incorporates the belief that cultural semantics and values that constitute public life are transmitted with and produced by symbolic practices, aesthetic experiences and media strategies that aim at actual embodied sensual patterns as the foundation of an affective experience of community. See Kappelhoff 2013.

The notion of modality, like register in socio-linguistics, defines a specific mode of aesthetic articulation adaptable across a range of genres, across decades, and across national cultures. It provides the genre system with a mechanism of ‘double articulation’, capable of generating specific and distinctively different generic formulae in particular historical conjunctures, while also providing a medium of interchange and overlap between genres (ibid.: 229).

The war film genre most basically addresses the melodramatic mode that encompasses the experience of suffering and compassion and provides cinematic forms of expression that shape the viewers’ emotions (cf. Kappelhoff 2013).

Scenes of suffering, agony and grief

Within the extensive research I did in the project, I observed that in the realm of the war film genre images of casualties are often connected to scenes that depict suffering, agony and grief. Here we have an example of a typical death scene in a classical Hollywood war film.

Clip 1: BATAAN (Tay Garnett, USA 1943): “The joint letter and the killed sailor” (01:40:22–01:42:00)

We can identify the obvious iconographic reference to Michelangelo‘s Pietà (4) in this example of BATAAN, a MGM war film from 1943 (Tay Garnett, USA).

It is important though to consider that in terms of the emotional mobilization of the addressed audience, scenes like this are constituted by expressive qualities of the audiovisual that unfolds as a structured experience of time. Within this structured experience we assume that a notion of agony and grief is articulated. This means that these scenes are not constituted on the mere basis of semantics or iconography. In this regard the research work in the afore mentioned project draws upon the concept of expressive movement which main characteristic is its temporal gestalt (5). Film theories as Eisenstein’s concept of the “fourth dimension” (cf. Eisenstein 1991a; 1991b) or Balázs’ concept of “the chords of the emotions” (Balázs 2010: 34) can be understood as having expressive movement as a central category. These theories are concerned with the relation between film and emotion in the form of a specific dimension of cinematographic movement. This notion combined with the concept of “embodiment” and neo-phenomenological film theory (cf. Sobchack 1992) enables us to have an understanding of how emotions are produced and shaped through a cinematographic process. According to this theory expressive movements are actualized as a bodily sensation. Vivian Sobchack describes this notion of “embodiment” within the theatre experience as following:

(5) This refers to a movement-image according to Plessner’s definition (cf. Plessner 1982: 77). For the use of the term expressive movement see Kappelhoff / Müller 2011 and Kappelhoff / Bakels 2011.

Experiencing a movie, not ever merely ‘seeing’ it, my lived body enacts this reversibility in perception and subverts the very notion of onscreen and offscreen as mutually exclusive sites or subject positions. Indeed, much of the ‘pleasure of the text’ emerges from this carnal subversion of fixed subject positions, from the body as a ‘third’ term that both exceeds and yet is within discrete representation [...] (Sobchack 2004: 66f.).

This in mind together with the just mentioned assumption of the fundamental importance of cinematographic movement signifies the correlation of the audiovisual composition of a film and an embodied sensation. Based on the audiovisual images that constitute the circulation of war imagery the project succeeded in making this audiovisual composition of a film describable with a method of standardized film analysis (6).

Images of civilian casualties in the newsreel United News

Before I will go into depth concerning the image of casualties in the newsreel format, I want to provide some basic information about the World War II newsreels that were produced during and shortly after the war, and which are the focus of my study. US-Military newsreels at that time emerged with the participation of the civilian film industry. Newsreels such as United News were produced entirely under military leadership, but their footage and often whole segments including the narration were used in diverse commercial newsreels such as RKO-Pathé News, Universal Newsreel and others (cf. Doherty 1999: 39 and Fielding 1972). Newsreels, as well as the documentary format of the combat report were compiled of images that were shot by military cameramen trained by Hollywood cinematographer units (cf. Doherty 1999: 262). Therefore it is not surprising at all to see, that patterns of Hollywood’s visual storytelling, as it is the case with continuity editing, were applied to the filmic documentation of military events. Let me give you some brief information about the particular format of United News. Usually one issue of United News has a running time of about ten minutes and is arranged in five to six segments. These segments resemble, what one might call news stories. All of them have headline-like titles. Issues of United News were released one to two times a week mainly for governmental affiliations but can be considered as the blueprint of all of the commercial newsreels of that time especially when it comes to war coverage.

It is important to understand the scope of newsreel distribution in wartime America. The public interest in war coverage was immense. For example, newsreels were shown in special cinema venues, that ran contemporary documentary formats all day. But it is important to emphasize that besides these special venues, war related documentary formats where shown consistently in combination with fictional films in commercial cinemas (cf. Doherty 1997).

I will continue now with the scenes of the war film that depict casualties and more specifically agony and suffering. On the basis of the already mentioned standardized film analysis (7). I found out that documentary formats such as the newsreel feature scenes of agony and grief that were very similar to the classical war film genre. For example, this is the case with the United News, the newsreel I focus on in this paper.

Here we have the diagrammatic display of what we call the affect-script, the sequence and constellation of pathos scenes according to their temporal arrangement within the film prepared on the basis of the mentioned standardized film analysis. This work is based on the realization, that the war film genre consists of a limited set of standard scenes as well in a narrative as an expressive sense we termed pathos scenes (8). By providing the framework of the systematic analysis of the classical Hollywood war film genre as an affective modulation of the viewer’s emotional involvement we are able to sketch an investigation of the war film genre within a wider historical scope. As it is the case with the last scene here, the combination of the pathos scenes is not unfamiliar to scenes in the classical war film. We have here a combination of the battle and technology scene, the scene of battle and nature and a scene of suffering-and-grief. The scene of the formation of a group body usually precedes the other scenes like these ones identified here, but in the condensed storytelling format of the newsreel this pathos scene was identified within one scenic complex together with the other pathos scenes.

Before I will go on with the image of casualties in documentary films, I want to outline, how we described the pathos scenes concerning casualties based on the classical war film. There we have at the one hand plot and character-constellations, that revolve around suffering and victims, on the other hand, we assumed, that these scenes are assigned to an affective dimension, that we qualify as agony and grief.

The further definitions of these pathos scenes according to our manual read as follows:

Short definition:

These pathos scenes share a focus on the soldier’s experience of bodily pain, vulnerability, and dying. The motif of suffering appears in three variations: the victim, the sacrifice, and the scene of suffering.

Constellations:

Victim: These scenes are about becoming aware of vulnerability and mortality, usually expressed as an unexpected moment of death.

Sacrifice: The soldier’s death is cinematically connected to a greater cause, the army, or the nation. Soldierly sacrifice is portrayed as a heroic death – often the death and the funeral are staged as the renewal of the community.

The scene of suffering: These scenes focus on the suffering individual who experiences himself as a vulnerable and mortal body. [...]

Affective Dimension:

[...] The inside view of an indissoluble, irreconcilable experience of suffering characterizes the central pathos of American war films [highlighted by DG] (9).

With that in mind I want to draw on a scene here that appeared in the in the final segment of the 76th edition of United News in 1943.

Clip 2: UN 076 “Australians in Dramatic Jungle Battle with Japs”.

The pathos of suffering and grief is realized along patterns of filmic expressions that account for a specific emotional mobilization. For reasons of space, I leave aside the detailed analysis of the films expressive qualities. The extracted scene demonstrates however, that with the newsreel-format we can assume a form of emotional mobilization of the addressed spectator beyond the mere intention of reconstructing historical events with the means of the documentary format.

So let’s have another look at the diagrammatic display of the affect-script of this edition of United News. There is another scene – the third one – that was identified as a pathos scene of suffering-and-grief, but this time without any combinations with other pathos scenes. We have no fighting scene, or any other pathos scene, that occurs at the same time with this scenic complex. This scene is also taken from the 76th edition of United News in 1943:

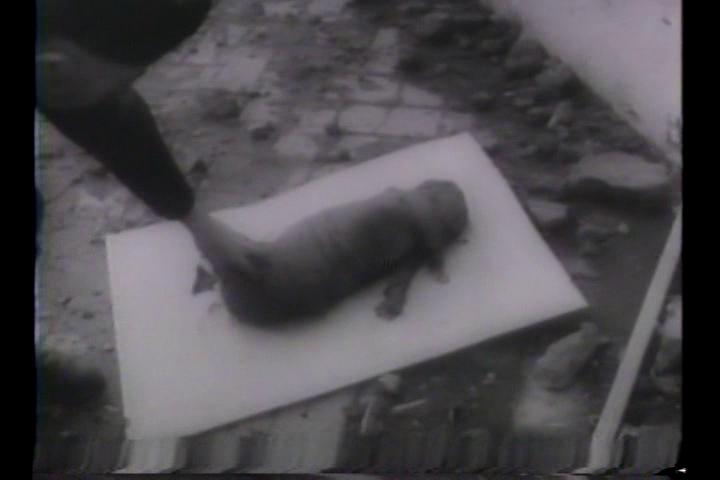

Clip 3: United News No. 076 (1943) “Italian Civilians Killed by Nazis in Naples Blast”.

This scene shows that with the newsreel-format we can assume a way of an emotional mobilization of the addressed spectator beyond the mere intention of reconstructing historical events. Here the notion of agony and grief is addressed on an emotional level of viewer engagement that is constituted by the audiovisual composition of the scene (10).

(10) For a detailed analysis of this scenes’ expressive qualities see http://www.empirische-medienaesthetik.fu-berlin.de/emaex-system/affektdatenmatrix/filme/united_news_076/03_terror_in_neapel/index.html.

When it comes to recurring motifs and characters in the case of scenes of “suffering-and-grief” in newsreels, it is striking that we often have on the one hand images of atrocities, which are unknown to the fictional war film genre. And on the other hand we have images of civilians suffering. As a motif, these images appear in the fictional films as well, but interestingly they occur far more scarcely. This is the case at least with the war films of the 1940s. The use of images of atrocities is often described in research literature as means of propaganda. This purpose of these kinds of images is rooted in what J. Michael Sproule, a professor in communication studies, relates to “atrocity stories”,which were one key element of World War I propaganda (cf. Sproule 1997: 1ff., 46). Susan Sontag, in her book Regarding the Pain of Others refers to Virginia Woolf’s book length-essay “Three Guineas”, when she concludes, that photographic images of atrocities, in that case images of the Spanish civil war, invoke a shared experience (cf. Sontag 2003: 6). An experience based on the shock of such pictures, that cannot fail to unite people of good will against war. Sontag also points out, that such images could also foster greater militancy, and this could be described as means of propaganda. I don’t want to argue, that we can compare such means of propaganda with the way the mobilization of emotions can point to a sense of community that we want to describe through genre dynamics. What is striking though is that the motif of the suffering civilian is almost always connected to images of children. Isolated from the scenes that depict “suffering-and-grief” the image of children is introduced as a recurring motif already in the fifth edition of United News.

In this edition foreign children literary arrive in the american society. In New York City they are welcomed and fed by the american public. This motif runs through the whole series of the United News.

The humanitarian duty towards underprivileged or suffering children is met by american forces by feeding the little ones, or by providing medical assistance. Many of these images were more or less staged for the camera. This becomes obvious when considering the placement of humanitarian goods within a well composed frame and the arrangement of American soldiers together with civilians within a specific shot. This was the case for example with United News No. 136 (1945).

On a semantic level, the accompanying voiceover commentary often alludes to a moral obligation towards foreign citizens, that are in need for help. But these images alone do not constitute that what I want to describe as an emotional mobilization. Therefore, I want to refer to another example of a scene of suffering that was included in an issue of United News. This scene and its preceding scene have at first glance nothing in common. Yet in their original consecutive order these scenes account for a semantic argument of the moral superiority of the United States and its allies.

Clip 4: United News No. 95.

The arrangement of these two scenes can account for what was depicted yet in another documentary format of that time. I am referring to the information films by Frank Capra. In the first instalment of his WHY WE FIGHT-Series an opposition of two worlds, the free and the slave, contrasts two different ideas of shared values.

An ideological conflict that is idealized by two contrasting globes. The semantically argument of a moral superiority occurs mainly in the succession of the two scenes of the newsreel. This argument also resonates in the second scene later scene in the conjunction of the figurations of the films audiovisual composition with the offscreen commentary narration, that constitute the specific quality of an aesthetic experience.

Here mainly through the combination of sound design with gestures and facial expressions. Central to the development of the affective dimension of this section however is the prominent use of the score in combination with the children's bodily expressions of sorrow. This example demonstrates that the documentary format of the newsreel draws explicitly on melodramatic modes known from narrative film. This analytical perspective might help us to understand how the emotional mobilization strategies cause a sensation, which is linked to the realization of affective and semantic complexes. In this way, abstract values are articulated. In the case of this United News edition it is the consensus of a shared value system, which is measured by the willingness of sympathy for the suffering innocents and the reassurance of a superiority of communal life, that constitutes the “free” world. It is a value system that is measured by the sympathy for the victims and is presented as a moral antithesis of fascist ideology of oppression of the weaker by the stronger.

The mobilization effect can be described within the newsreels’ audiovisual composition, as that it makes sensible the committed injustice in the theater of war, which is attributed to an individual reality of the addressed viewer, that is, the moral duty to intervene. I would like to emphasize the fact now that in regard to the practice of staple programming theses modes of viewer engagement where complemented or even mirrored within the actual location where genre films and newsreels were screened at the same time.

To conclude what these implications hold for the specific historical framework that constituted the emotional mobilization during World War II. I want to provide a deeper look at how in wartime America the composition of a staple program might have looked like in an actual theatre (cf. Doherty 1997). For this I draw upon the description of Frank Ricketson: The Management of Motion Picture Theatres, published in 1938 (cf. Ricketson 1938). It’s a handbook for theatre owners. There Ricketson gives advice for sequencing different contents within a single and a double bill program. The following represents the ideal arrangement of different elements within a film theatre program of the late 1930s according to Ricketson (cf. ibid.: 120f.).

Staple program for a single feature house:

- One-reel subject

- Newsreel, Announcement trailer on coming attractions or policy

- Two-reel Comedy or short subject

- Announcement trailer on next attraction

- Feature

- Intermission

Staple program for a double feature house:

- Announcement trailer on coming attractions or policy

- “B” Feature

- Newsreel

- Announcement trailer on next attraction

- “A” Feature

- Intermission

Based on studio release dates I filled in the blanks, so one can have an idea of how the staple program might have looked like. It is of course only a hypothetical programming but still not that unlikely.

Staple program. Single feature house, example Universal, late 1943 / early 1944:

- One-reel subject: MEATLESS TUESDAY (genre: animation, approx. 7 minutes)

- Newsreel, Announcement trailer on coming attractions or policy: Universal Newsreel (approx. 10 minutes)

- Two-reel Comedy or short subject: SWEET SWING (genre: musical, approx. 20 minutes)

- Announcement trailer on next attraction

- Feature:

- GUNG HO! (genre: war film, approx. 88 minutes)

- Intermission

Staple program. Double feature house, example Universal, late 1943 / early 1944:

- Announcement trailer on coming attractions or policy

- “B” Feature: CALLING DR. DEATH (genre: horror film, approx. 63 minutes)

- Newsreel: Universal Newsreel (approx. 10 minutes)

- Announcement trailer on next attraction

- “A” Feature: GUNG HO! (genre: war film, approx. 88 minutes)

- Intermission

Moviegoing experience

In light of these observations I would like to propose the expression moviegoing experience that – as I will try to show – can help to distinguish the characteristics of the staple program in its historical context in terms of an aesthetic practice.

Since the last decade the theoretical conceptualization of the term moviegoing was in the focus of many historiographic studies of the cinema. For example, the HOMER network, that consists mainly of exponents of the new film history – a line of research that gained popularity in the 1980s (cf. Allen / Gomery 1985 and Salt 1983) – explicitly asks for ways of combining the terms “moviegoing”, “exhibition” and “reception” in a historical trajectory (11).

(11) The depiction of the network‘s goals, that has Douglas Gomery, Richard Maltby, Robert C. Allen and others as its members, reads as following: “The History of Moviegoing, Exhibition, and Reception – or HOMER – Network (formerly “Project”) is an international network of researchers interested in understanding the complex phenomena of cinema-going, exhibition, and reception, from a multidisciplinary perspective.” See http://homerproject.blogs.wm.edu/ [19.01.2015].

A closer look at these undertakings reveal that the inherent task to put into perspective paradigms of spectator theories with a historical concept of cinema could still be developed further (12). Yet more than ten years before the HOMER network started its activities two researchers of the University of Chicago explored the intersection of spectator theory and film historical research in depth. I am referring to the work of Tom Gunning and Miriam Hansen. Gunnings concept of the “cinema of attractions” helped to release histories of early cinema from mere genealogy. His aim was to describe the “nature of film spectatorship” (Gunning 2006: 38; see also Gunning 1990) along historical shifts. Mainly it was Miriam Hansen though who connected theoretical concepts of film spectatorship to a perspective on film history in her monograph Babel and Babylon. Spectatorship in American Silent Film (Hansen 1991).

(12) In June 2013 I attended a workshop by the HOMER-Project, that was held at the NECS-conference in Prague. I also attended a number of presentations of projects that are associated with the HOMER-Project at that same conference. Even though there were many intriguing approaches in terms of “moviegoing” and “exhibition”, it appeared to me, that theoretical and methodological questions concerning the issue of “reception” could still be addressed to a greater extend.

With the example of the Nickelodeon of the first decade of the 20th century Hansen examines in her own words “the conditions of cinematic reception in terms of theater experience” (ibid.: 90). She assumes that the cinema’s impact on the spectator is rooted not just in the screened film but in a specific act of presentation and the actual circumstances of film reception. According to Hansen these circumstances of film reception constitute a specific framework of a shared experience in a public sphere. The cinema understood as a cultural practice produced new ways of subjectivity and intersubjectivity that informed a “particular kind of collectivity actualized in the individual viewing experience” (13).

I want to illustrate this notion by referring to an excerpt of Preston Sturges’ 1941 comedy SULLIVAN’S TRAVELS (USA).

(13) “Neither a primeval paradise of viewer participation nor merely a site for the consumption of standardized products, the cinema rehearsed new, specifically modern forms of subjectivity and intersubjectivity at the same time that it addressed older needs and more recent experiences of displacement and deprivation. If it assumed both of these functions, it did so not only because of the liminal situation of its audiences and its own threshold status among commercial entertainments but also because of the particular kind of collectivity actualized in the individual viewing experience” (Hansen 1991: 105).

Clip 5: SULLIVAN’S TRAVELS (Preston Sturges, USA 1941), 01:18:00–01:23:31.

Here the protagonist at first stands out of the crowd.

He then recognizes the projected film as some kind of a counterpart within the viewing situation.

He then assures himself among the surrounding spectators of his own sentiments, by noticing his very own reactions to the projected film. After that he shares this experience with the other patrons, still reassuring himself of his own sentiments in comparison with the group in the auditorium.

This depiction can help to better understand what Hansen pointed out in regards of the specific theatrical experience that is about a “spectatorial disposition that is at once absorbed and active, at once self-abandoning and very much part of the situation of exhibition” (ibid.: 106). In this regard, interestingly, Hansen’s idea of spectatorship can be associated with the auspices of an embodied film experience. Within the paradigm of neo-phenomenological film theory Vivian Sobchack attributes the “cinesthetic subject” as a way of experiencing the films projection as an audio-visually bound perception that holds a special place for the viewer within the films presentation:

[...] the cinesthetic subject both touches and is touched by the screen – able to commute seeing to touching and back again without a thought [highlighted by VS] and, through sensual and cross-modal activity, able to experience the movie as both here and there rather than clearly locating the site of that cinematic experience as onscreen or offscreen. As a lived body and a film viewer, the cinesthetic subject subverts the prevalent objectification of vision that would reduce our sensorial experience at the movies to an impoverished ‘cinematic sight’ or posit anorexic theories of identification that have no flesh on them, that cannot stomach ‘a feast for the eyes’ (Sobchack 2004: 71).

What both approaches have in common is the positioning of the viewer within a space that can no longer be described in terms of a perception of the everyday world but is rather constituted within the boundaries of a specific aesthetic experience. This is because Hansen’s heuristic assumption on that aspect of spectatorship is rooted in the extensive theoretical discussions concerning the term of public sphere. She names in particular Oscar Negt’s and Alexander Kluge’s monograph Öffentlichkeit und Erfahrung as a point of reference (cf. Negt / Kluge 1972; English version: Negt / Kluge 1993). Based on Negt’s and Kluge’s assumptions Hansen regards the cinema as a place were a public sphere can be realized because it enables the patrons to share and negotiate their very own lived-in world (14). This experience is distinct in its historical background. Negt and Kluge even regard the possibility of alternative public spheres that root in the communication of the conditions of the lived-in world of an individual segment of society. With this in mind Hansen draws upon the group of east coast immigrants of the 1900s. Based on the fact, that many immigrants visited Nickelodeon theaters on a daily basis, Hansen draws the connection between a specific spectatorial disposition and the negotiation of an alternative public sphere that is realized in the experience of moviegoing. In her comprehensive study Hansen depicts the theatrical space of the cinema along individual “exhibition practices” (cf. Hansen 1991: 93ff.) as a space were immigrants were able to articulate and negotiate a shared experience of social isolation. Hansen is well aware of the fact, that it is difficult to draw conclusions on experiences of moviegoing of a long gone social group. Yet in the depiction of the genuine and vintage practice of cinema exhibition Hansen sees the possibility to reconstruct a social experience within a specific historical framework that was shaped by an aesthetic experience of moviegoing:

(14) See also Kappelhoff 2008.

[...] it is difficult to know how these groups – or, for that matter, any group – received the films they saw and what significance moviegoing had in relation to their lives. Still, we can try to reconstruct the configurations of experience that shaped their horizon of reception, and ask how the cinema as an institution, as a social and aesthetic experience, might have interacted with that horizon (ibid.: 101).

It is in this regard that I want to use the term moviegoing experience. This experience is bound to the historical distinct features of the film‘s exhibition that can be described as a specific practice. In terms of the images of casualties that I examined in this study the practice of staple programing is instructive when it comes to trace and understand a historically grounded experience of the american society in World War II. This experience is shaped by the circumstances of the staple program in connection to the aesthetic experience based on the idea of embodied film reception that I described earlier. Within the staple program there is the juxtaposition of similar yet different images of sorrow and grief that surface within the documentary and fictional formats and begin to compose one evening‘s shared experience. This constitutes a space where the patrons negotiate a shared experience of the lived-in world with its wartime realities that accounts for a public sphere that is genuine to its participants. This means that I do not necessarily focus on an individual social group like Hansen did. I rather pursue to take into perspective the vast net of theater chains and playhouses on a national level that embraced the exhibition practice I described as staple programming (15). Considering the film industry’s impact on making the abstract nature of war accessible for cinemagoers at home, the wartime mobilization of the American public can at least partially be accounted for by the closed realm of staple programming.

(15) I currently elaborate this approach in my PhD thesis with the working title “Tickets to War” at the department of Film Studies at Freie Universität Berlin.

Conclusion

Taking into account the observations on the scenes of “suffering-and-grief” in the Hollywood war film genre and the newsreel-format, the pathos of the suffering, dying soldier has an equal counterpart in the pathos of the suffering civilian victim.

Both images of victims are confronted within the staple program. In fictional genre films, representations of the suffering soldier are tied to the pathos of the sacrifice that connects the soldiers’ death to a higher cause. In these scenes the guilt of a nation to its dead or fatally injured enlisted citizens, who secure its freedom, is articulated. On the other hand, the addressed compassion with the civilian victims in the documentary formats is bound to the moral duty of the nation, that is – one could say – to intervene when injustice is done.

This indicates two aspects of the emotional mobilization of wartime American citizens. Images of atrocities that were excluded from the fictional genre film were included in war coverage. Thus a blank space in genre cinema re-emerged in the staple program. By emphasizing what genre modes of representation omitted, the institutionalized distribution practice of staple programming helped to re-negotiated the nature of a shared experience of war.

Bibliography

Allen, Robert C. / Gomery, Douglas: Film history. Theory and practice. New York 1985.

Arendt, Hannah: Lectures on Kant's political philosophy. Chicago 1982.

Balázs, Béla: Visible Man or The Culture of the Film. In: Erica Carter (ed.): Béla Balázs. Early film theory. Visible man and The spirit of film. New York 2010, 1–90.

Cavell, Stanley: Cities of words. Pedagogical letters on a register of the moral life. Cambridge 2004.

Doherty, Thomas: Documenting the 1940s. In: Thomas Schatz (ed.): Boom and bust. The American cinema in the 1940s. New York 1997, 397–421.

Doherty, Thomas: Projections of war. Hollywood, American culture, and World War II. New York 1999.

Eisenstein, Sergei: The Filmic Fourth Dimension. In: Jay Leyda (ed.): Film Form. Essays in Film Theory. London / New York 1991a, 64–71.

Eisenstein, Sergei: Methods of Montage. In: Jay Leyda (ed.): Film Form. Essays in Film Theory. London / New York 1991b, 72–83.

Gunning, Tom: The Cinema of Attractions. Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde. In: Thomas Elsaesser (ed.): Early cinema. Space, frame, narrative. London 1990, 56–62.

Gunning, Tom: Attractions. How They Came into the World. In: Wanda Strauven (ed.): The cinema of attractions reloaded. Amsterdam 2006, 31–39.

Kappelhoff, Hermann: Realismus. Das Kino und die Politik des Ästhetischen. Berlin 2008.

Kappelhoff, Hermann: Kriegerische Mobilisierung. Die mediale Organisation des Gemeinsinns. Frank Capras PRELUDE TO WAR und Leni Riefenstahls TAG DER FREIHEIT. Navigationen. Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturwissenschaften 9 (2009), 151–165.

Kappelhoff, Hermann: Der Krieg im Spiegel des Genrekinos. John Fords THEY WERE EXPANDABLE. In: Hermann Kappelhoff, David Gaertner, Cilli Pogodda (eds.): Mobilisierung der Sinne. Der Hollywood-Kriegsfilm zwischen Genrekino und Historie. Berlin 2013, 184–227.

Kappelhoff, Hermann / Bakels, Jan-Hendrik: Das Zuschauergefühl. Möglichkeiten qualitativer Medienanalyse. zfm - Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft 5 (2011), 78–95.

Kappelhoff, Hermann / Müller, Cornelia: Embodied meaning construction. Multimodal metaphor and expressive movement in speech, gesture, and in feature film. Metaphor and the Social World 2 (2011), 121–153.

Negt, Oskar / Kluge, Alexander: Öffentlichkeit und Erfahrung. Zur Organisationsanalyse von bürgerlicher und proletarischer Öffentlichkeit. Frankfurt am Main 1972.

Negt, Oskar / Kluge, Alexander: Public Sphere and Experience. Toward an Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere. Minneapolis 1993

Norris, Andrew: The claim to community. Essays on Stanley Cavell and political philosophy. Stanford 2006.

Plessner, Helmuth: Die Deutung des mimischen Ausdrucks. Ein Beitrag zur Lehre vom Bewußtsein des anderen Ichs. In: Helmuth Plessner: Gesammelte Schriften VII. Ausdruck und menschliche Natur. Frankfurt am Main 1982, 67–130.

Ricketson, Frank H.: The management of motion picture theatres. New York / London 1938.

Rorty, Richard: Achieving our country. Leftist thought in twentieth-century America. Cambridge 1998.

Sobchack, Vivian: The address of the eye. A phenomenology of film experience. Princeton 1992.

Sobchack, Vivian: What My Fingers Knew. The Cinesthetic Subject, or Vision in the Flesh. In: Vivian Sobchack (ed.): Carnal thoughts. Embodiment and moving image culture. Berkeley 2004, 53–84.

Sontag, Susan: Regarding the pain of others. New York 2003.

Filmography

BATAAN. Tay Garnett. USA 1943.

CALLING DR. DEATH. Reginald Le Borg. USA 1943.

GUNG HO! Ray Enright. USA 1943.

MEATLESS TUESDAY James Culhane. USA 1943.

SULLIVAN'S TRAVELS. Preston Sturges. USA 1941.

SWEET SWING. Josef Berne. USA 1944.

TAG DER FREIHEIT – UNSERE WEHRMACHT. Leni Riefenstahl. D 1935.

United News No. 5 (1942)

United News No. 76 (1943)

United News No. 95 (1944)

United News No. 136 (1945)

WHY WE FIGHT. Frank Capra. USA 1942–1945.

.jpg)

affect-script.jpg)

affect-script.jpg)

.png)

.png)