Jennifer M. Barker

Their eyes meet. Sparks fly. Passion ignites.

Romantic melodrama often depicts romance as a kind of electric charge or galvanic force, and this is certainly true in Todd Haynes’s CAROL (USA 2015), which recounts the story of a love affair between the title character – a suburban socialite, wife, and mother – and a younger woman, Therese, an aspiring artist and temporary department store clerk in mid-century New York. (1) Critic A. O. Scott calls the film “a study in human magnetism, in the physics and optics of eros. [...] [T]he current of feeling passing between Carol and Therese as they chat over their teacups,” he says, “is so strong that the air around them seems to vibrate.” (Scott 2015)

(1) This is an expanded version of an essay that appeared as Barker, Jennifer M. Click. Affect and Mediated Gestures in Carol, edited by Anne Rutherford. The Cine-Files 5/10 (2016). http://www.thecine-files.com/barker2016/.

In Haynes’s film, the physics and optics of eros are literal, and material, conducted and conveyed in the mise en scène. Of course, a focus on mise en scène seems fitting in the case of a director who is always so keenly focused on the look of his films, on costume, decor, female performances in particular, and production design. (Indeed, the headline of one review of the film forecast, correctly, that “Everyone Will Be Talking about the Cars and Clothes of CAROL.” [Allen 2015]) But I do not mean mise en scène in the traditional, rather static sense of that term.

I am inspired by recent approaches like those of Anne Rutherford, who posits that mise en scène is synonymous with “energetic process [...] That organic unity, that elusive quality of flow and energy that moves a film and moves us as spectators with it.” (Rutherford 2012: 305, quoted in Martin 2014: 18) Adrian Martin recently pointed out that a good and memorable “classically structured work” – and I would put CAROL in that category – often “cannily systematizes into a meaningful pattern what are ordinary, everyday gestures and actions: walking, eating, driving, and so on.” (Martin 2014: 24)

Walking, eating, and driving: in fact, that is nearly everything that happens in CAROL. We might only add smoking and flirting to round this out. And it is in these gestures that the affective charge of the romance – both positive and negative – circulates most forcefully. More specifically, in Haynes’s film, passion leaps between bodies and lively objects and back again, always conducted through a series of precise gestures performed by the two lovers as they engage with these material things – trains, cars, telephones, record players, radios, cigarette lighters, a suitcase, a gun, and a camera, to name a few.

This paper focuses on two of these objects – the train and the camera – and the affective, mediated gestures in which they are involved. What I mean by “gesture” here has as much to do with the objects themselves as it does with the actresses’ movement, and with editing and sound, for example. In this sense, I am looking for a pattern of what Hermann Kappelhoff and Cornelia Müller refer to as “expressive movement,” not “as intentional or involuntary proof of the inner orientation of a human subject,” but as “an expressive behavior on the part of all living beings, conceived as an interplay of affective exchanges of intensity. Expressive movement comes about as a direct matching of affective alignments between individualized bodies.” (Kappelhoff / Müller 2011: 134)

The film’s production design, costuming, and soundtrack are stunning in their attentiveness to the tones and textures of things like fur coats, vintage décor, and tinny radio broadcasts. But the film’s attentiveness to materiality and its keen sensitivity to affective relations between humans and objects are as much Patricia Highsmith as they are Haynes. In The Price of Salt, the short novel from which the film is adapted, Highsmith’s language sparks with the energy created by friction between objects and humans, like the estranged husband’s overcoat slung over a loveseat in Carol’s front hall, “sprawled open with its black arms spread as if it were fighting and should take possession of the house,” (Highsmith 2015: 57) or the wind that “flung itself around the tall cement corner of Frankenberg’s [department store] as if it were furious at finding no human figure there to oppose.” (Highsmith 2015: 46) It is telling that Haynes and screenwriter Phyllis Nagy kept the bit of dialogue in which Therese’s friend describes the laws of human attraction. “We’re like pinballs,” he says, “bouncing off one another. [...] Not everything reacts. [...] But everything is alive.”

Like Haynes, Highsmith dwells on material details of texture, color, and heft. She often entertains an object’s implicit capacity to affect or be affected by other bodies, as when Therese nervously drops a child’s doll onto the glass countertop in the toy department while showing it to Carol. “Sounds unbreakable,” Carol quips (Highsmith 2015: 29). Not surprisingly, given the hard-edged tone and penchant for subtle cruelty in Highsmith’s crime fiction, there is an implied violence in many of these instances.

There is a hard edge, as well, to the lovers’ relationship in Highsmith’s novel. It is fraught with tension, not all of it sexual, though there is certainly that. Their encounters are often tinged with impatience and vague irritation on Carol’s part, and she can be quick with a cutting remark, “her voice soft and even, and yet merciless.” (Highsmith 2015: 152) When Therese timidly shares some of her sketched designs, Carol casually offers a brutal critique; “she could demolish a set with a phrase,” thinks Therese (Highsmith 2015: 139). Over their first lunch together, “she wanted to look at the woman’s mouth, but the gray eyes so close drove her away, flickering over her like fire.” (Highsmith 2015: 36) Nevertheless, she cannot help but be drawn to the flame: “Therese took some more of her drink, liking it, though it was like the woman to swallow, she thought, terrifying, and strong.” (Highsmith 2015)

In fact, Therese’s adoration of Carol takes on a violent edge, as well. On a drive through the Lincoln Tunnel toward Carol’s suburban home, Therese “wished the tunnel might cave in and kill them both, that their bodies might be dragged out together.” (Highsmith 2015: 47) Later that day, in an odd moment both innocent and tensely intimate, Carol insists the exhausted young woman take a short nap in the guest bedroom. Therese acquiesces, “not caring if she died that instant, if Carol strangled her.” (Highsmith 2015: 51)

The fierceness that subtends their romance – as crucial to its passion as their mutual affection and desire – resonates with Highsmith’s descriptive emphasis on the brute force and aggressive energy of material objects. The sharp rap of a cigarette lighter on a glass-topped table expresses Carol’s unspoken anger when Therese initially, stubbornly refuses her invitation to join her on the road trip, in one scene. Later that same evening, Carol will remark to Therese, “You’re about as weak as this match,” holding one up and letting it burn after she lights a cigarette. “But given the right conditions, you could burn a house down.” (Highsmith 2015: 113)

Haynes and screenwriter Nagy may seem to have smoothed over much of the friction between the two women that crackles through Highsmith’s novel. The director admitted, in one interview, that the couple needed to be made more “compatible” in their transition to the screen, to make the story more marketable. (2) Indeed, some have critiqued the film for being merely “handsome, respectable, predictable,” (Fry 2015) overly concerned with surface and style, and “a far more conventional venture” (Rosman 2015) than its source novel.

(2) “What you try to do is make it more congenial to a financier,” said Haynes. “And so everything felt a little more kind of … compatible … with the two women right away. And I loved the tensions in the book.” (Pride 2015)

But it is precisely in the charged interplay between humans and objects that the film renders the emotional and sociohistorical complexity of the women’s relationship. By tracing the movement of this affective charge across and through certain gestures – the flip of a switch, the press of a button, or the turn of a key, for example – we find that the propulsive, even violent, force of passion not only circulates between the characters and objects, but also, and more profoundly, characterizes the film’s own material and temporal structure. And at that level, we see that what may appear to be a classical, even conventional, romantic melodrama in fact presents what Gilles Deleuze would call a “line of flight,” arcing outward from the long, linear tracks laid by the genre conventions of the romantic drama.

Strangers and a Train

Haynes tips his hat to a number of romantic film conventions and classics, not least of which is David Lean’s BRIEF ENCOUNTER (United Kingdom 1945). As many critics have noted, he borrows from it a neat narrative trick: namely, he opens the film with a private conversation that is casually interrupted by a passing acquaintance, a conversation whose momentous emotional impact we learn only by returning to it after a feature-length flashback. He also borrows a central motif: a train that runs through the lovers’ relationship from the start. Of course, there is a long history of cinema featuring trains as a symbol for romance and sex, from romantic melodrama (BRIEF ENCOUNTER, Max Ophüls’s LETTER FROM AN UNKOWN WOMAN [USA 1948]) to romantic comedy (TWENTIETH CENTURY [Howard Hawks, USA 1934] and THE LADY EVE [Preston Sturges, USA 1941]), to the romantic thriller (Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 NORTH BY NORTHWEST [USA] being the iconic example with a sardonic edge). The examples are probably countless.

Whereas the train in BRIEF ENCOUNTER screams through the station, spewing a phallic plume of white steam as it passes the camera, Haynes’s trains appear only at a remove, and they operate much less straightforwardly. They initiate an affective movement that gets taken up in other forms, by other figures, in ways that both drive the narrative forward along the straight tracks leading toward a conventional ending and, at the same time, leave open alternative possibilities.

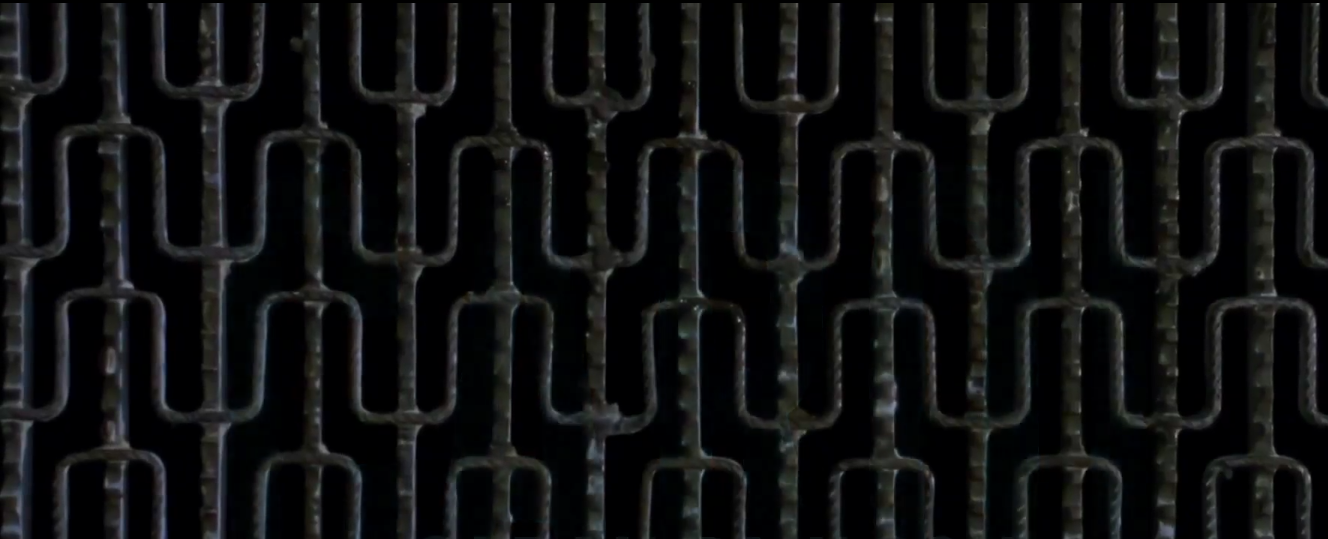

The first train appears obliquely, rumbling onto the soundtrack even before the first image fades in on an intricate design. The image is abstract and unrecognizable until the camera pulls slowly away, revealing the gray geometrical pattern of a subway grate (Fig. 1), from which steam rises to mingle with a growing crowd that rushes up and out of the station and into the street and the evening light.

Several minutes later, after Carol and Therese’s conversation over tea in the hotel has been cut short, we see Therese seated in the back of a taxicab. Again, the sound of a train, rather than its image, appears. The rumble of an approaching train blends with traffic noise to form a subtle sonic background, as she recalls the first time she laid eyes on Carol. (Fig. 2–3)

This reminiscence initiates the flashback that takes up a good portion of the film. The next scene sees Therese some months earlier, working a morning shift at Frankenberg’s, during which we see their first meeting unfold in real time.

That first encounter begins when the store opens for business on a day just before Christmas 1952. A crowd spills from the elevator onto the sales floor and scatters in every direction, children pulling parents to this display and that one.

Against the relentless movement and collective energy of the people passing in front of the camera at close range, Carol’s first appearance is strikingly placid, her only movements a casual tug to loosen her scarf and a slight settling of her hips.

In fact, it is the movement of another woman that initially leads the camera to Carol. As this anonymous woman exits the frame, the panning camera stops and refocuses on Carol in the background. (Fig. 4–7)

Seconds before Therese and Carol’s eyes meet across the crowded room, the toy train that speeds around the track in front of Carol comes to a complete and sudden stop. It is interesting that nothing interferes with the train to make it do this: it just stops.

Carol turns to look for the switch that powers the train, then looks up, glances around with an expression of bored imperiousness, and catches Therese’s mesmerized stare.

Their intense focus as they hold each other’s gaze is exaggerated by the shoppers who pass by, blocking our view and their views of each other. (Fig. 8–11)

Further accentuating Carol’s stillness among the chaos is the whip-pan, in which Therese’s attention is dragged away by the mother and child. Another whip-pan follows, again from her point of view, as her gaze races back to the spot where Carol had stood. When Carol reappears out of nowhere a moment later, she throws down the gauntlet, quite literally. The slap of her fine leather gloves against the countertop brings Therese to rapt attention, and the rest of the scene unfolds as a private encounter between them, the hum of the crowd diminishing in the background. (Fig. 12–16)

In The Washington Post’s description of that first meeting in the toy department, Carol and Therese “have a perfectly unimportant interaction about dolls and toy trains, ending in a sale, when something cataclysmic happens: Carol turns on her way out, smiles slyly and, pointing to the Santa cap Therese wears with obvious discomfort, says, ‘I like the hat.’ It’s an electrifying moment.” (Hornaday 2015)

Far from being unimportant, it is the toy train that causes the initial eye contact, not simply or solely the characters’ desire. This is the cataclysmic event that sets the romance into motion. The train is literally electrified and “electrifying.” Its own lively affective force, to which Highsmith devotes considerable attention in the novel, leaps across the gap between object and character to be taken up in the encounter between Therese and Carol, and this happens well before any flirtation or even interest on Carol’s part.

Full Stop

In this sense, the train is an example of what Rutherford describes as a film’s “material elements – landscape, decor, etc. [acting] as energetic units, as potential units or sparks of experiential energy.” (Rutherford 2004) The train’s sudden stop brings Carol up short, setting in motion a chain reaction. Its affective intensity carries over into both Carol’s and the camera’s movement as they turn and tilt, looking for the switch, and then to her direct gaze at Therese, who must respond – and does, with that second, searching look after her gaze is momentarily pulled away.

Carol and Therese “click” in this scene, not in the sense of making an immediate, unambiguous connection, like a circuit being suddenly closed, but in the sense of coming to a halt, however momentary. In other words, the “turn on” that occurs in this scene is at least partially predicated on a “turn off.”

Highsmith gives that little train a long, wonderful paragraph of its own, where she writes, “In the jerk of its nose around the curves, in its wild dashes down the straight lengths of track,” one “could see a frenzied and futile pursuit of a tyrannical master. [...] It was like something gone mad in imprisonment, something already dead that would never wear out, like the dainty, springy-footed foxes in the Central Park Zoo, whose complex footwork repeated and repeated as they circled their cages.” (Highsmith 2015: 6)

In coming to a full stop (which happens only in Haynes’s version, not Highsmith’s), the train seems to resist the general frenzy of the department store and the shoppers who descend on the toy department. In doing so, it initiates an affective movement that Carol and Therese take up, though not consciously. The meeting of their gazes is not only an instantaneous mutual attraction, then, but also an affective response to the train’s own agitation and, in turn, a resistance to a general pattern of busy, repetitive, restless, collective movement on the part of crowds surging through train stations, streets, the hotel, and the department store in the film’s first ten minutes, going through the motions that mid-century American consumerist culture demands of them.

Both are caught up in these movements themselves, of course – Therese bounces like a pinball from one counter display to another, distractedly searching for a doll that will please her customer, and Carol reaches for a cigarette to calm her jittery nerves, all the more flustered to be told she cannot smoke on the sales floor. In responding to the futility of its endless racing around the track, the train emits a current that carries over to Carol and Therese, both of them desperate to jump the tracks of polite, class-based consumer culture that keeps them caged like a pair of sharp-toothed, “springy-footed foxes” on display.

This “click” is only one part of a more elaborate pattern that structures the narrative of their romance and at the same time complicates it and exceeds it, as I will show. The pattern is predicated on collision, shock, suspension, stillness, and dynamic action. The full stop not only enables the space and time for a reaction; it demands one. In this respect, the train’s gesture is the model for the women’s relationship more broadly, giving eros what Adrian Martin, in his study of eroticism in and at the cinema, calls its particularly cinematic “experiential shape.” (Martin 2012: 526)

The relationship between the two women unfolds as a series of propulsive moments in which anything might happen. For every action, there is a pause, then a reaction, often unpredictable and decisive. Carol slaps the gloves on the countertop to get the younger woman’s attention, then leaves them behind; Therese picks them up and drops them in the mail. Carol invites her to lunch, then to her home, then on a cross-country road trip; to each invitation, Therese surprises Carol with a frank, unwavering “Yes.” Therese surreptitiously takes a photograph of Carol; later Carol calls her on it, and Therese stops what she is doing, mortified; this prompts her to admit, all but directly, her attraction. Carol then buys her a new camera, and the first photo Therese takes with it is of Carol, right out in the open. Carol demurs, but Therese stops her with an uncharacteristically brazen touch and a gentle command: “stay like that.” At a roadside motel, Carol orders two separate rooms; Therese counters quietly, “Why not take the presidential suite? If the rate’s attractive.” Carol’s double-take reveals stunned delight at Therese’s having upped the ante, a bold move all the more enjoyable for the hotel clerk’s inability to see this forward move for what it is.

Haynes’s film easily lends itself to discussion of the particularities of a “female gaze,” (Cochrane 2016) but Highsmith’s novel emphasizes the degree to which this female gaze is marked not only by desire but confrontation; it is not merely flirtatious but literally provocative. Across the table on their first lunch date, for example, Highsmith’s Therese sees “curiosity and a challenge, too” in Carol’s eyes, which “could be tender and hard at once, as they tested her.” (Highsmith 2015: 200) Late in the novel, Therese presses Carol on the truth of something she says, and the tension is unmistakable: “‘That’s what I said.’ Carol replied with a smile in her eyes, but Therese heard the same hardness in it as in her own question, as if they exchanged challenges.” (Highsmith 2015: 204) The flinty contestation here does not forestall their passion whatsoever, in this scene or any other; it is constitutive of it.

Again and again, Carol’s gestures take on the feeling of a dare, as when, with a flirtatious sideways glance, she enjoins Therese to invite her over to see her photographs, or coyly slides the gifted suitcase across the threshold of Therese’s apartment with one outstretched foot. Therese has the power to bring Carol up short, as well. Recalling her own nervousness during their first outing, for example, “Therese glanced at her. ‘I was so excited about you,’ she said. [...] Then she looked at Carol again and saw a sudden stillness, like a shock, in Carol’s face. Therese had seen it two or three times before when she had said something like that to Carol.” (Highsmith 2015: 150)

The train’s stop/start gesture, which sets in motion this affective pattern between the lovers, is subtly anticipated very early in the film by the soundtrack that accompanies Therese’s recollection of their first meeting at Frankenberg’s. As she stares out the window of the taxicab, we hear the sound not only of a train, but of impending danger: the warning bells of a nearby railroad-crossing “clang” loudly and the approaching train’s whistle screams, before it roars past at top volume.

The sound coincides with and continues over the film’s cut to the first image of the flashback itself, in which the tiny toy train rushes past the camera in extreme close-up. After a few shots of the toy train racing through its miniature village, the dreamy flashback cuts to Therese behind the doll counter. She looks up and her gaze is arrested by Carol’s presence. At that moment in the flashback, the real present-day train screams past on the soundtrack, and the film cuts back to Therese in the taxicab, looking pensive and sad.

The editing here makes the sound poignantly ambiguous: it is both the sound of the actual train and the affective, if imaginary, sound of the tiny toy replica. Sliding between present-day reality and the romantic fantasy of the past, the sound of the train simultaneously underscores the violent effect of Carol’s presence in the past scene and jolts Therese out of her reverie in the present one.

In this flashback and the first meeting itself, Therese would appear to be the passive recipient of the affective charge that passes from the train to Carol to herself, were it not for one of Haynes’s subtlest changes to Highsmith’s story. In the latter, Therese seems merely to sympathize with the train. As Highsmith writes, “Nearly every morning when she came to work on the seventh floor, Therese would stop for a moment to watch a certain toy train. Its wrath and frustration on the closed oval track held Therese spellbound. The train was always running when she stepped out of the elevator in the morning, and when she finished work in the evening. She felt it cursed the hand that threw its switch each day.” (Highsmith 2015: 5) In the film, however, Therese is the one who sets it in motion, as part of her early morning routine at Frankenberg’s.

This tiny train carries considerable weight: specifically, it takes on two things missing from the novel. The conflict Highsmith emphasizes between the two lovers, which is absent from a screenplay designed to be palatable to its financiers, and the hostility of the train itself, which in the novel had been aimed at an anonymous “tyrannical master,” are condensed into the single stop/pause/start gesture of the train, which comes to life at Therese’s touch and stops cold with Carol’s arrival.

Of course, the train’s feisty stop serves the narrative by bringing together the couple, but at the same time it creates a suspended space-time in which affect gathers and transforms, to be released in an unforeseen direction. The meeting of their eyes across the crowded room reads as “romance” but cannot be understood apart from the affective charge of the mediating machinery that shaped it. In this way, as Elena del Río writes in her study of performance and affect, “in the gestures and movements of the performing body, incorporeal forces or affects become concrete expression-events that attest to the body’s powers of action and transformation.” (del Río 2009: 3f.)

All this is quite different from reading the train as a metaphor in any abstract sense, or as an element of the mise en scène in the conventional, concrete sense. As Rutherford writes, in reference to the literal translation of mise en scène, “While objects can be ‘put onto the stage’ in theatre and be expected to maintain their integrity as solid objects, no such assumption can be made in cinema. [...] An object does not maintain its status as an object once it is in the frame: colour or a set are not merely background – they are by definition part of the ensemble of experience of the spectator, constituted in and through the temporal experience of a scene/a shot.” (Rutherford 2004)

Within the larger category of mise en scène, Martin delineates an aspect he calls “social mise en scène,” which seems especially relevant for a film like CAROL given its keen interest in depicting the social mores of early 1950s America through subtle details of gesture and speech. Social mise en scène includes a film’s array of individually performed but culturally coded “gestures, settings, physical actions, and the peculiarly cinematic rendering of these elements.” (Martin 2014: 25) It is not simply, he writes, a matter of “admiring the easy way in which a star like Humphrey Bogart, Robert Mitchum or Gena Rowlands walks down the street, lights a cigarette, or casts a look that could kill [...] [T]here is much, much more going on in the human body’s cultural business of carrying and expressing itself.” (Martin 2014: 138f.)

In Alexandre Astruc’s 1959 definition of the term, mise en scène is “a certain way of extending states of mind into movements of the body. It is a song, a rhythm, a dance.” (Astruc 1985: 267)In CAROL, it is a “click” – a sudden full stop, a pregnant pause, and a propulsive movement in response. That affective movement always involves humans and objects, many of which are mechanical that are themselves in motion, like the train and the camera.

Don’t Blink

Perhaps the most significant alteration Haynes’s film makes to Highsmith’s novel, and the one that first sparked my interest in the characters’ relations to material objects, is in Therese’s artistic aspirations. In the novel, Therese is an apprentice theatrical set designer, but in the film, she is an aspiring photographer. It is in her role as a photographer that the affective pattern initiated by the train gets taken up, in ways that subtly frustrate the romantic narrative’s relentless drive toward resolution.

Phyllis Nagy rewrote Therese as a photographer in her screenplay adaptation of the novel, completed well before Haynes’s involvement in the project, but Haynes’s own passion for the aesthetics and, more important, the politics of photography is well established (see Stasukevich 2015). This film, more than any of his others, emphasizes the mediated nature of interpersonal relations in 1950s urban life in part by way of its distinctly photographic look, borrowed predominantly from the work of street photographer Saul Leiter. Additionally, Haynes looked to female photographers of the day – Ruth Orkin, Esther Bubley, and Helen Levitt, in particular – for visual inspiration, gesturing toward a specifically female gaze at urban life. (3) Here, however, I will focus not on the look of photography, but the act itself: the photographic gesture.

(3) Todd Haynes interview with Rolling Stone Senior Culture Editor David Fear, CAROL, BLU-RAY: StudioCanal 2016.

In his phenomenological description of a variety of human gestures, Vilém Flusser calls the gesture of taking a photograph a quintessentially intersubjective act, in the sense that the photographer takes up a position inside the situation and is, at the same time, reflectively aware of the possibility of seeing that situation from another position inside it (that is, from the “subject’s” position as object of the camera’s gaze), and yet another position outside it, from many points of view, though one can never physically occupy a point of view other than one’s own at a given moment. This, he says, “is the basis for a consensus, for intersubjective recognition.” (Flusser 2014: 141)

For Flusser, the shutter-click is part of the camera, purely mechanical, therefore not part of the human gesture of taking a photograph. For philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, however, the press of the shutter-button is part of the gesture; it is the most interesting part, because it brings into relief the defining tension in the photographic gesture between distance and contact, which co-exist in that split-second. In that tiny “click,”

the thing that or the one who “takes” the photo and the thing that or the one who “is taken” in the photo are suspended together. [...] Both are taken by each other and by surprising or coming upon each other. They are there, intimate and intrusive, strange and familiar to each other, at the same moment, as the same image. (Nancy 2005: 104)

(4) For an extended discussion of the significance of Nancy’s account for moving image studies, see Ahnert 2017.

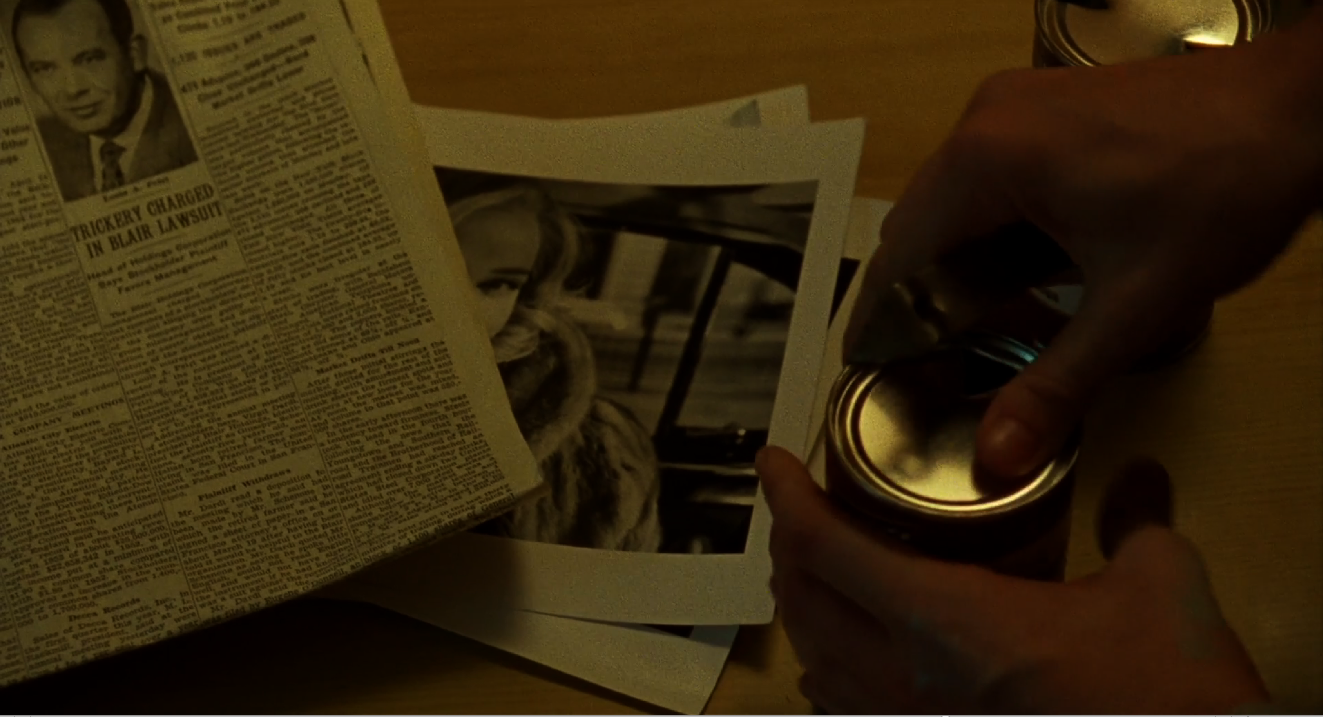

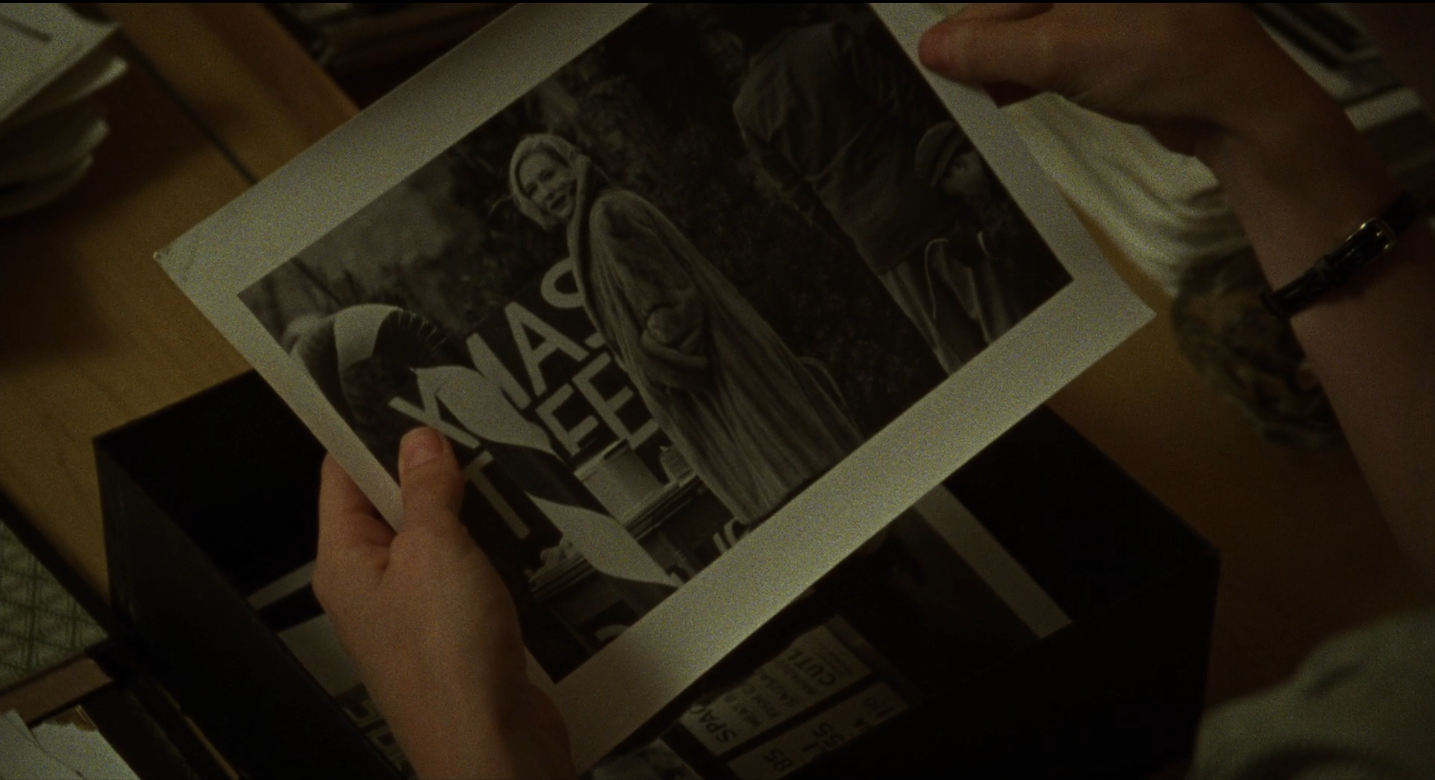

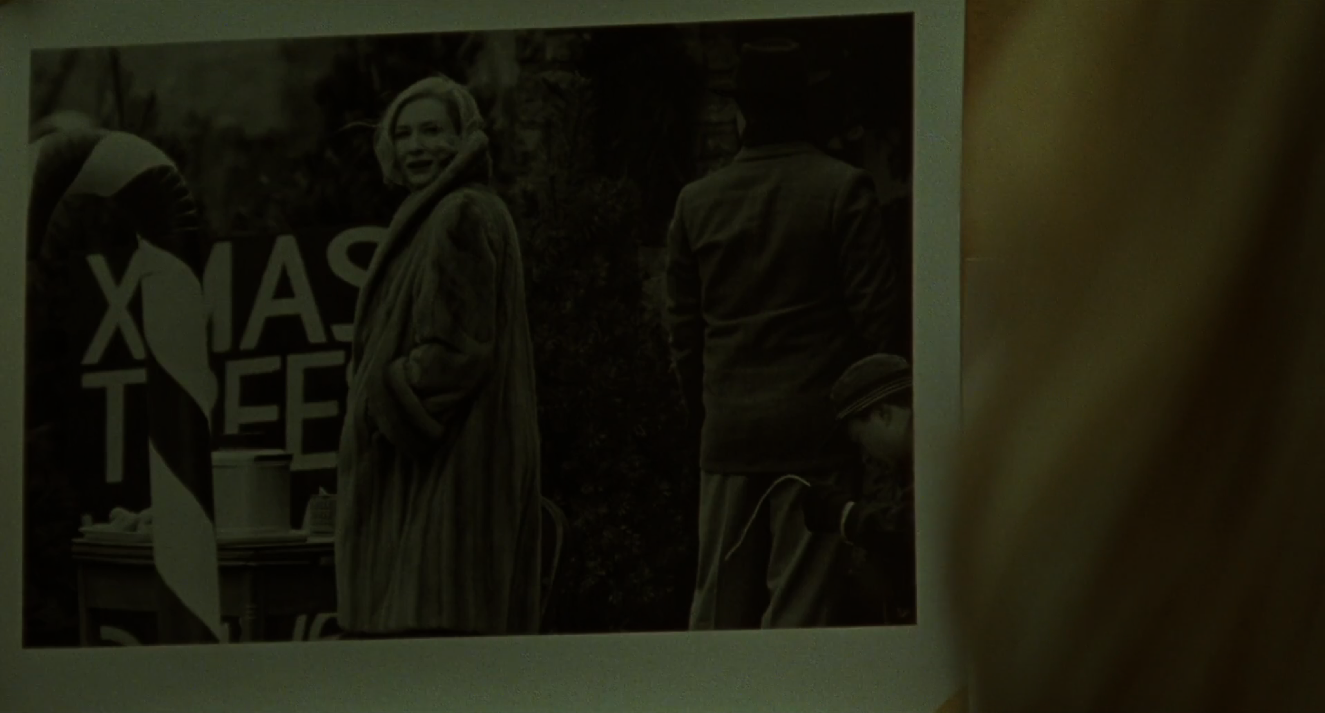

The photographic gesture is an important part of Carol and Therese’s relationship. (Twice Therese points a camera at someone else – once at her boyfriend, Richard, and once at her friend and hopeful suitor, Dannie – but both are empty gestures, as there is no film in either camera.) Carol is the first and only subject we see Therese shoot, and we see many of the resulting photographs as well, as when Dannie visits the apartment and admires a stack of prints inadvertently left on the kitchen table. (Fig. 17–18)

Therese’s printed photographs of Carol are lovely, but rarer and more interesting are the moments in which we witness Therese actually taking a photograph. If the romantic (and romanticizing) portraits we see in printed form support a reading of the film as a conventional love story, the shutter-click itself serves to counteract it, as did the ornery train and the complex exchange of gazes it sparked. The pressing of the shutter-button opens a sliver of space-time that Nancy calls “a grasping: this thing, that thing, this man here, that woman there was grasped, there, at that time, by a click,” prior to those relations being fixed in a printed photograph (Nacy 2005: 105).

Therese’s photographic gesture, then, is a set of movements and decisions that culminates precisely in the pressing of the shutter-button – the moment of “grasping” in which this woman “here” and that woman “there” are caught up in what Nancy calls a “sovereign hesitation” (Nancy 2005: 105).

When Therese photographs Carol for the first time, we see this gesture play out in detail. (Fig. 19–28)

The scene takes place in a Christmas tree lot, where Carol and Therese have stopped on their way to Carol’s suburban home, the day of Therese’s first visit. Therese, who is opted to stay warm and dry in the car, loads a film roll into her camera, and takes two shots of Carol, both of which we see through her viewfinder as she focuses and composes them.

Later in the film, after the lovers have separated, we will see the printed photograph Therese made of this moment. Thus, logically speaking, one of the two shots she takes in this scene must be the shutter-click that ultimately results in that particular printed photograph.

For the first shot she takes in the tree lot, the shutter-click occurs off screen: we hear the “click” but only cut to a shot of Therese and her camera a split-second after the sound. By the time we get to this shot of Therese, she is already lowering the camera to advance the film.

For the second image she shoots, the press of the shutter-button and the resulting “click” occur on screen: we see and hear them simultaneously. Thus, one would think, this is the shot/moment in which Therese snaps the image we later see in printed form. But this cannot be.

The printed photograph Therese produces from this scene is a medium close shot of Carol’s direct gaze, looking over her shoulder as she turns away from the camera (Fig. 29), but neither of those details can be true of the two shots Therese takes in that scene. Firstly, only Haynes’s camera gets close enough to produce that image. Therese is too far away to do so, as is made clear by the point-of-view shot through the windshield.

In stepping out of the car, she does not move any closer, and her camera (which she later tells Carol is “not even decent”) does not have a zoom lens. Secondly, Carol’s turn and direct gaze toward Therese happen neither precisely in conjunction with the shutter-click we hear, nor within a split-second of the press of the shutter-button we see. Thus, the printed photograph that results from the scene, over which Therese lingers later, is impossible.

Whether the slippage is a minor (very minor) cinematic gaffe or an insightful point by a filmmaker well known for his media savvy and predilection toward critical reflexivity is less important than its effect, which is to illustrate precisely the difference between the photographic gesture (including the shutter-click) and the photograph. (5)

In his 2008 essay “Gesture and Abstraction,” Blake Stimson argues that the work of Robert Frank exemplifies the radical ambivalence of a particular photographic gesture that developed in the 1950s and that essentially turned the documentary quality of documentary photography outward and inward in the same instant.

(5) In what may or may not be a coincidence, the Christmas tree lot in which this photographic conundrum develops closely resembles the one in which Sarah Jane confronts Annie in IMITATION OF LIFE (Douglas Sirk, USA 1959). More to the point, this conundrum is identical to one that occurs in Sirk’s film, in which photographer Steve Archer’s camera cannot possibly have taken the photograph of the girls at the beach that the film attributes to him. As in Haynes’s film, the slippage is provocative (see Barker 2014).

That complex look came together in an instant as an amalgam of several interrelated gestures that we might artificially separate here as follows: first, the movement of the finger depressing the shutter, an action that might at once be understood as aggressive toward its object, like the squeezing of a trigger, and defensive of its subject, like the nervous blinking of an eye; second, the turning away of the photographer’s body and attention from that view as it is being captured on film; and third, the turning inward of the photograph’s attention from the world outside to his own affective response. This complex is on view everywhere in Frank’s pictures––in their fleeting, reaching, and distancing quality, in their taught [sic] mix of fascination and repulsion, in the nervous glance of photography on the run, and in the constant turn of the photographer’s and beholder’s attention to motifs that carry the aesthetic or affective charge of a void or full stop. (Stimson 2008: 78)

The day after this trip to the tree lot, Carol visits Therese’s apartment, where she examines several photos haphazardly taped to the kitchen wall. The tree lot photograph is among them, and Carol gives this a long look. (Fig. 31) “I can do better,” says Therese, apologetically. “I was rushed.” She was not, of course: the photograph reflects not lack of time but the “nervous glance” and mix of “fascination and repulsion” Stimson attributes to this photographic gesture (where “repulsion” might describe Therese’s own ambivalence toward feelings she cannot name and that she has been told, by boyfriend Richard and others, are unnatural).

Stimson appreciates the way Frank’s images seem to stretch out the instantaneous and simultaneous movement of the gaze outward and inward. “What Frank did that none of his followers were able to sustain at the same high level was to do both outside and in at the same time in a way that made them seem both fully vested and inseparable. That is [...] he was able to sustain the mediation. His inimitable appeal seemed to be born of this all happening in the bodily movement of the photographic act itself, in the decisive moment of the click of the shutter.” (Stimson 2008: 77) (6)

(6) Stimson refers here, of course, to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment.” The essay contrasts the two artists’ approach to this moment and posits that the ambivalence created in Frank’s photographic gesture parallels a more genuine move toward negation and subjectivity that parallels a similar gesture in critical theory.

In the tree lot, Therese lowers the camera and her face takes on a thoughtful expression: as with Stimson’s examples from Frank’s oeuvre, the photographer’s outward gaze turns immediately to the photographer’s own affective response to the look, the gesture expanding, elongating the space-time between these two poles. Therese’s photographic gesture, too “carries the aesthetic or affective charge of a void or full stop” in this way, just as the train’s abrupt stop had provoked a collision of gazes, a challenge, and a suspended moment of shock and stillness full of potential and fraught with violence.

Staring at Therese’s photograph of the tree lot moment, Carol ignores the younger woman’s apologies. After a long look, she claims “it’s perfect.” She is right: it is perfect, impossibly so. The printed photograph from this dreamy interlude is, in this sense, much like the happy ending and full closure of a romantic melodrama.

However, the “perfect image” is not the one Carol examines in this scene, but the one that does not exist at all. It cannot exist: the unique temporality of cinema makes it impossible. Therese’s press of the shutter-button, which we do not experience from her point of view, is thus a perfect gesture of pure potential. It contains within it the “hesitations” among and between subject (and object) positions in the photographic encounter, the “grasping” of each by the other. It stages in a single instant, and in a way a printed photograph cannot replicate, the tumultuousness of the dynamic between Therese, Carol, and the camera.

In this sustained mediation, this elongated tension, the “click” thus expresses both the dialectic between cruelty and desire in Highsmith’s novel, and the critical embrace of romantic melodrama we find in Haynes’s film, which recognizes what Jonathan Goldberg calls the “impossible situation of melodrama,” whose happy endings depend upon the impossible resolution of irresolvable differences, not only between social categories and identities, but also and more profoundly within the individual, within identity itself. Sirk acknowledged that, in this respect, his films’ happy endings were, as Goldberg puts it, “delusional.” (Goldberg 2016: 49)

“People shouldn’t be what in German is called eindeutig,” Sirk said. Eindeutig: unequivocal, unambiguous, unmistakable, singular in meaning, self-identical. It seems significant that Sirk describes his notion of identity through a German word, as if what he has to say escape the singularity of a language. [fn] “Intermediate” is the English term perhaps used most often in conversation with Halliday, although “split” and “in-between” also recur as terms for nonsingular identity. (Goldberg 2016: 25, quoting Halliday 1997: 70)

Of the photographic gesture in Haynes’s film, we might say what Goldberg says of a passage in Beethoven’s Fidelio, which its score calls a “Melodram”: “this melodramatic passage is a very unsettled and unsettling interval and [...] that is what it is about –– not some underlying truth waiting to be revealed, but an inhabitation of the irresolutions, the what-ifs and as-ifs. [...] These hesitations, suspensions, and doubts play out in the words spoken and in musical passages that are themselves sometimes at cross-purposes, resolving, unresolving.” (Goldberg 2016: 7) Here, the hesitations and suspensions play out within the photographic gesture, whose intrinsic ambivalence Haynes heightens by cutting into it, creating the gap between the sight and the sound of Therese pressing the shutter-button so as to “suspend the mediation” as in Robert Frank’s photography, pausing the process by which the “encounter” would become the “photograph,” a fixed image, just one of many caught up in a narrative moving relentlessly forward to its conclusion.

Tender Buttons (with Apologies to Gertrud Stein)

Stimson also refers to the ambivalent, simultaneously inward- and outward-directed photographic gesture as the “switch” or the “relay” between subjectivity and objectivity. That the women’s gazes meet for the first time immediately after the camera’s swift tilt downward to the train’s switch, the one Therese herself had flipped hours earlier, emphasizes the way this gesture travels along and between mechanical bodies and human bodies alike: the press of the shutter-button, the sudden stop and start of the train, and the collision of the women’s gazes mark precisely this instant in which subject and object become “strange and familiar to each other, at the same moment, as the same image.”

The affective power of the train and the camera, then, is taken up by the characters and the film more broadly. It is worth noting that this same affective gesture – the sudden stop, the pause, the potential, and the propulsion into movement – is also produced by Carol’s car, the phonograph, the radios, and several telephones, and it gets caught up and expressed, too, in specific mediated gestures both women, but especially Carol, make as they engage with these things.

Of the glorious Packard that features so prominently in the film, production designer Judy Becker says “the car represents freedom. On their road trip, they can escape from the society that they live in.” (7) But the car does more than that; it functions not only as a symbol in the limited sense Becker describes and beautifully visualizes; more importantly, the car participates in the affective movement I have been describing. In fact, Highsmith and Haynes both devote considerable attention to the car and to Carol’s driving. The fact that Highsmith’s Carol teaches Therese to drive (at Therese’s request) over the course of their cross-country road trip – a road trip many days and nights longer than the one in Haynes’s film – and later leaves Therese with the car for the remainder of the story, such that their eventual reunion is structured around the necessary return of the car to its owner, should make clear the significance of driving as a theme, both for the originating story and for Haynes’s adaptation.

(7) Judy Becker interview, CAROL, BLU-RAY: StudioCanal 2016.

Haynes and Highsmith perfectly visualize one of my favorite aspects of film noir, which is the way femme fatales handle magnificent cars with such sexy confidence. (They may be fatale, but when they kill you it will not be by car accident: these dames can drive.) Highsmith offers this description, from Therese’s point of view, of being taken for a ride in Carol’s car: “It was like riding inside a rolling mountain that could sweep anything before it, yet was absolutely obedient to Carol.” (Highsmith 2015: 46) The resolute control Carol manages over her car only slips once, when she and Therese embark on their road trip: here, the car seems as giddy as they are, careening a little as it makes the turn out of the slippery, snowy driveway.

Later, Carol’s ex-husband sends a private eye to track them, prompting Carol to turn around and begin the drive back from Iowa to New York, where a custody battle awaits. Therese’s sudden outpouring of despair prompts Carol to pull the car over and, for no reason that makes any narrative sense whatsoever, she brings it to a full stop. (On this highway in Iowa, Haynes does not pretend there is any traffic for her to avoid.) This full stop is entirely affective on both sides: emotionally driven with mechanical effect, and mechanically expressive of human emotion.

That full stop is narratively and literally pivotal: we find out only later that, as she pulls the car over, Carol is already planning to leave Therese, a betrayal that will send the younger woman into a tailspin. Carol assures Therese this is “not your fault,” but fault does not matter: things have been set in motion that now must be reversed (though, of course, they cannot). When the engine turns, Carol blows out a frustrated breath, and Therese miserably coughs up a little cloud of smoke: all three “bodies” – both women and the car, whose entanglement the film and novel have made very clear – are caught up in that same propulsive but also literally exhausting movement forward and back, reversing the forward motion of their romance, by now well underway.

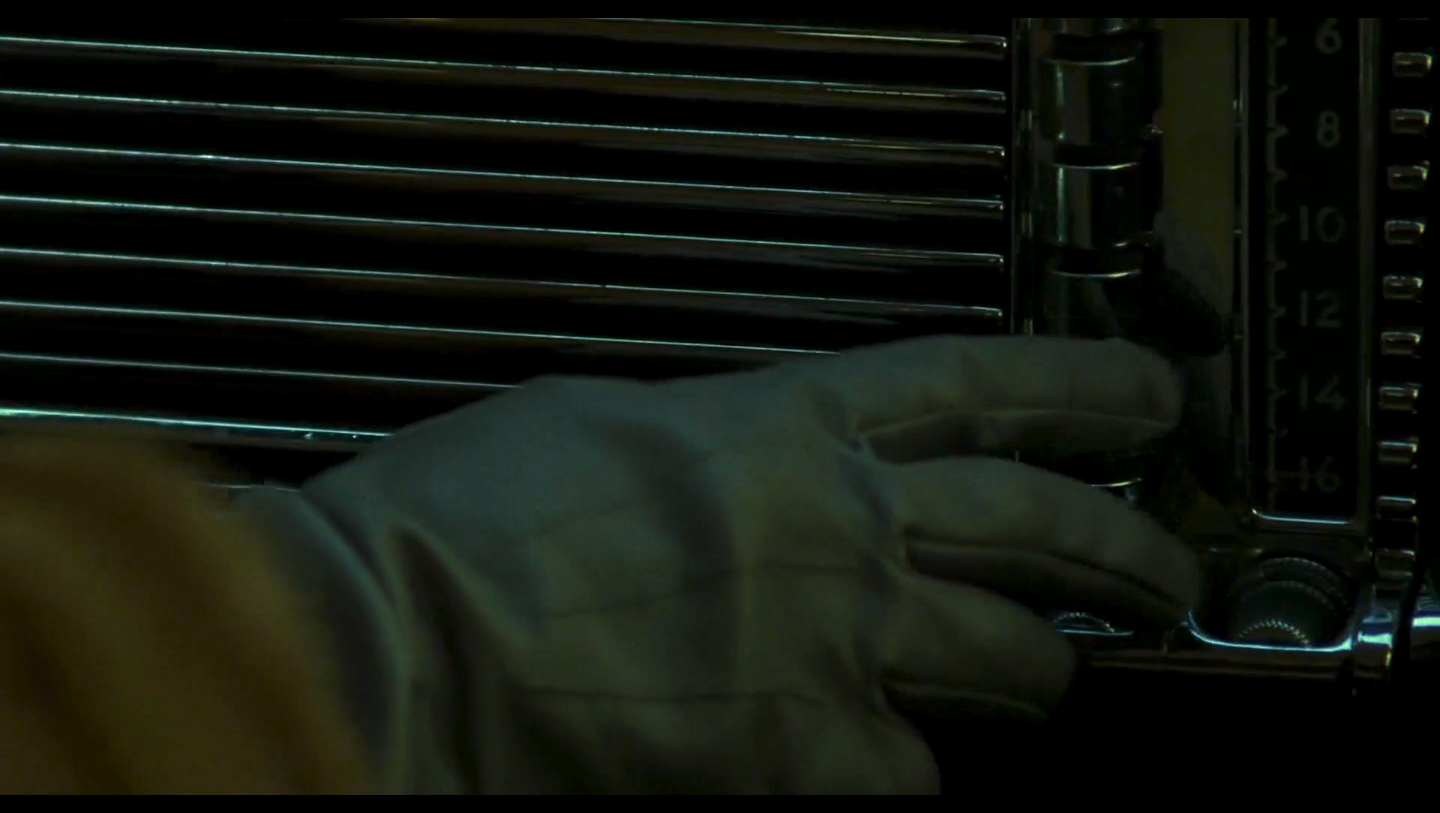

Like the car, the radios in the film also seem affectively tuned to and engaged in the charged encounters between the two women. As Carol drives Therese to her suburban home, she reaches out with a gloved hand to turn on the radio, as Therese quietly swoons next to her.

The force of their attraction alone turns on the radio, apparently, and conjures up the romantic tune, because as many New Yorkers could tell you, there was no radio reception in the Lincoln Tunnel in 1952. Conversely, on New Year’s Eve in a cheap roadside motel in Iowa, they listen to the New Year’s Eve celebration and “Auld Lang Syne” on a tabletop radio. The radio mysteriously turns itself off precisely when Carol (finally) takes Therese to bed, its music fading away without anyone having touched it. Perhaps the radio, too, has been made breathless with excitement, as the soundtrack gives way to a hushed silence and then the romantic theme music that accompanies the lovers’ first tryst.

These are the first and third radios to appear in the film. The second radio is perhaps the most poignantly expressive. Late at night, somewhere along the drive from New York to Ohio, with Therese asleep beside her, Carol listens to a broadcast describing the scene at the Eisenhower’s home this Christmas Eve: the newly elected president has put aside politics to focus all his attention on the grandchildren who gather at his feet with their presents. What would Christmas be, the announcer asks, without children and family? In this case, the radio intrudes on Carol and Therese’s growing intimacy, rather than responding to it. The broadcast hits too close to home, reminding Carol of the child she has been forced to leave behind and the conventional lifestyle she is expected to embrace. Carol punches the power button and, in the ensuing silence, reaches across to pulls the car blanket more closely around Therese’s shoulders.

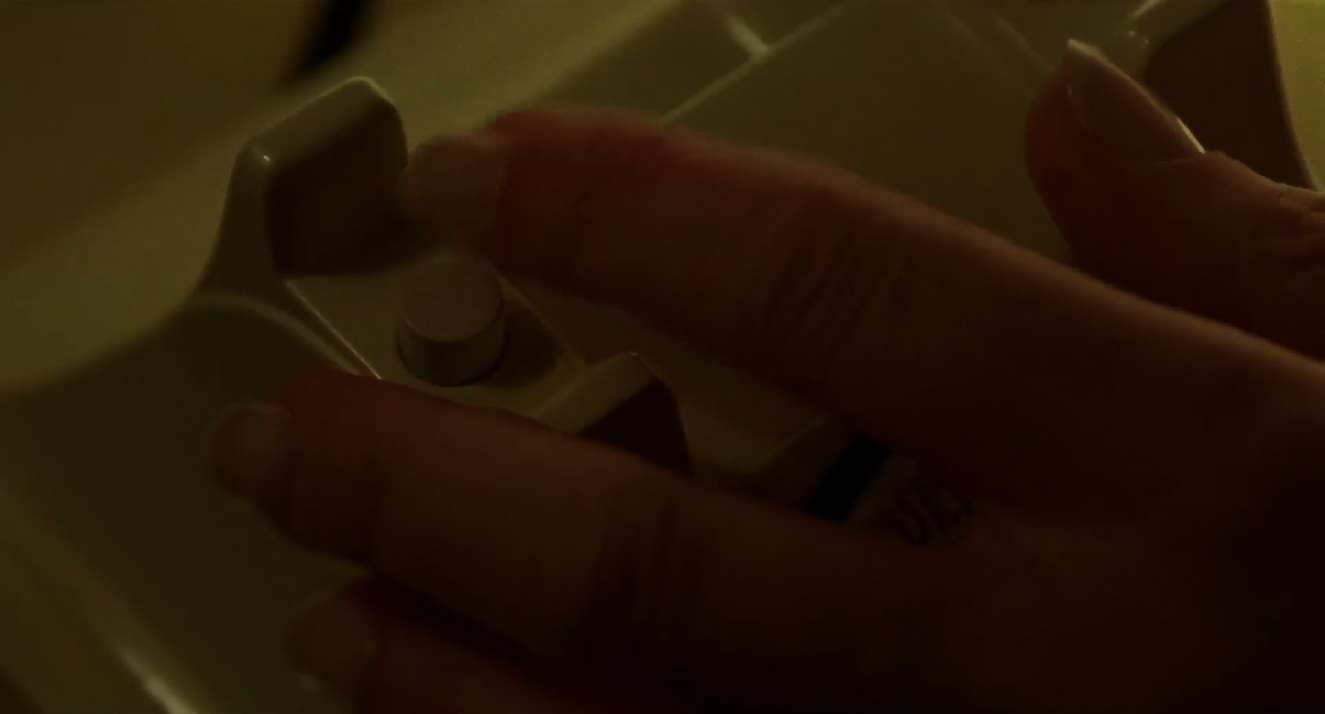

Then there is the telephone, of which we see many. Flusser points out that the telephone permits “a gesture no other dialogic medium permits”: for one party to silence the other by hanging up (Flusser 2014: 141). Indeed, Carol hangs up on Therese not once, but twice. Both times, we see what Flusser describes as “the brutality of this gesture” but also its intimacy and mutual vulnerability (Flusser 2014: 141). Flusser argues that the gesture of telephoning is absolutely not intersubjective: one caller initiates the call, one merely receives it, and in the case of the hang-up, someone always hangs up first. In their phone conversations, however, Carol and Therese shift between these two positions.

When Carol calls Therese to make amends after an abrupt end to their evening at the house, for example, Therese presses the phone to her chest to wait out the commotion of her rowdy neighbors returning home, but Carol hangs up before Therese can return. Much later, weeks after their separation, Therese places a tentative call and Carol picks up but remains silent for a long, agonized moment. Her manicured fingertip wavers over and against the edges of the switch-hook as she listens to Therese’s voice, before finally, reluctantly severing the connection, but even then, Therese whispers into the silence as if she could keep the line open. (Fig. 35–36) Thus, what Nancy writes of the press of the shutter-button is true also of the telephone’s switch-hook in these scenes: “by pressing down, the finger says I; it suspends the hesitations between the multiple subjects intersecting and mixing.” (Nancy 2005: 101)

If critical responses to CAROL emphasized in nearly equal measure the actresses’ performances and the film’s production design (“the cars and clothes of CAROL”), perhaps this is because bodies and objects engage with one another affectively by performing and taking up the same gestures. As Laura Mulvey writes, “the filmic body on display also exhibits the cinematic machine in a fusion of the human and the mechanical.” (Mulvey 2015: 10) Specifically, the “‘in between-ness’ that characterises the fragment or the freeze-frame has a parallel in the aesthetics and significance of gesture.” (Mulvey 2015: 6f.) Cate Blanchett’s and Rooney Mara’s performances in CAROL exemplify this parallel: their most evocative moments consist of flickering glances, hesitant gestures that hover on the edge between stillness and motion, inward and outward, always emphasizing the pivotal in-between.

Flung Out of Space

The affective energies expressed in these gestures, which circulate between humans and objects throughout the film, are disruptive, but admittedly only to a degree. As Elena del Río points out, the power of affective performance in moving images, as conceived within a Deleuzian and Spinozan framework, “is hardly a question of performance restoring agency to an individual character or a particular social group; instead, it is a question of the film’s mobilization of performance as the catalyst for the dissolution of (narrative, ideological, and generic) meaning in a more abstract, less personalized way.” (del Río 2009: 17)

The affective gestures I have traced here are not radically asubjective or anti-representational in the way some cinematic affects are. But neither are they mere “symbols”; the “click” is not just a metaphor for a romantic attraction, but a profound, affective movement – both material and metonymic – that moves within and alongside a classical narrative structure but occasionally strays from it, leaving open a space for movement in an unforeseen direction. This, Nancy says, is the nature of the photograph itself:

The secret of the photograph, the very clear mystery of its being lost and straying, is its flight into the strange in the very midst of the familiar. [...] By capturing its own straying, it leads what it captures astray. The photograph estranges, it estranges us. (Nancy 2005: 106)

These affects constitute a line of flight of sorts, against what Michele Schreiber calls the “intoxicating allure of the traditional ‘happy ever after’ resolution,” and away from the conventional notion of the couple that often accompanies it. (Schreiber 2014: 4)

Goldberg lauds the “aesthetic of impossibility” and negation he finds in Haynes’s films and in those of his predecessors:

“The most beautiful melodramas,” writes Todd Haynes, “like those of Sirk and Ophuls, are the ones that show how the worlds in which those characters live – and the happy endings foisted on them – are wrong. And like all those shimmering objects crowding the screen, the answer always lies in what’s missing.” What’s missing? Haynes declines to say. If it is missing there is no word for it. Melodrama inhabits this locale, a space in whose extraordinary negations arise further questions, inarticulate inextinguishable feelings, the possibility of impossibility. (Goldberg 2016: 35, quoting Haynes 2003: XIV)

What is missing has no name and no image, but it leaves an aperture, a tiny opening that marks its absence. Therese’s photographic gesture in the tree lot produces one of these: the tumultuous, ambivalent encounter that cannot be captured, its absence marked by a false image – the perfect, printed photograph – that stands in its place. The film doubles and triples that negation with two non-diegetic photographic gestures of its own, separate from Therese’s.

The first of these comes just before that scene, as Carol and Therese drive out of the city. The scene unfolds like a dream, a gauzy blend of sidelong glances and captivating details – a blond mink coat sleeve, a vividly seductive smile – brought into and out of focus with the dizziness of lustful fascination. The romantic tune dominates the soundtrack, the two women’s voices muted beneath it. At the end of this brief interlude, the tunnel, the music, and the car disappear to make way for the scene at the Christmas tree lot. The transition occurs through a fade out to white screen – brief but noticeable – and a fade in to color and noise, to the sound of a car speeding past as we see Carol looking glamourous, standing in center-frame amidst the lush green of the tree lot. That momentary white-out is a promise, an image of pure potential, an affective echo of Therese’s hopeful optimism.

The second of these non-diegetic photographic gestures constitutes the very last image of the film, or rather, the lack thereof. In the final scene, Therese has refused Carol’s invitation to start again and live together in the city, but now she rushes to the restaurant where Carol had told her she could be found, if Therese should change her mind. She sidesteps the flustered maître’d and enters the large dining room to make her way slowly through a sea of elegantly dressed diners. The romantic musical theme sweeps on the soundtrack, oboe and clarinet rising and falling in concert. Restaurant patrons pass close by the camera, as had the shoppers in the toy department, impeding her gaze, but this time the scene unfolds in slow motion. The camera tracks with her in medium close-up and slow motion, revealing every flicker of emotion as she seeks out the familiar face.

A clearing opens around a table in the near distance, and there Carol sits, engaged in conversation. Therese stops, her expression softens, her eyelashes flutter just once, and as if sensing her presence, Carol looks up. Their eyes meet, Carol begins to smile, and ... nothing. (Fig. 37–38) Immediately, the film cuts to black and to utter silence, withholding both the critical, punctuating chord of the musical theme and any decisive gesture that might, or might not, secure their reunion. Like Beethoven in Goldberg’s account, Haynes uses the melodramatic moment not “for the revelation of identity, nor for the resolution of action, but to sustain irresolution.” (Goldberg 2016: 9)

As Patricia White writes of the ending’s delicious ambiguity, “the lovers remain in their exclusive, eternally present tense, while the viewer is given both a tantalizing taste of the past and glimpse of a queer future,” which “promises further cycles of desire and loss.” (White 2015: 17) In place of a happy ending, the film offers an un-ending, like a shutter-click that produces no image. Indeed, the earlier white-out and this final cut to black are precisely, respectively, the images that would result from an interrupted photographic gesture, in which the shutter stopped while fully open or fully closed.

In the light (rather, in the darkness) of this dramatic finale, one of the film’s and novel’s most remarked-upon lines begs a second glance. Twice Carol remarks that Therese seems “flung out of space.” The first time she says it, during their initial lunch date, it is a bemused description of this strange girl. Later, in bed in a motel room in Iowa, it is a stunned expression of amazement and love. Highsmith’s description of their first tryst, however, encourages us to take it a bit more literally. She writes,

it was pale-blue distance and space, an expanding space in which she took flight suddenly like a long arrow. The arrow seemed to cross an impossibly wide abyss with ease, seemed to arc on and on in space, and not quite to stop. Then she realized that she still clung to Carol, that she trembled violently, and the arrow was herself. (Highsmith 2015: 162)

Given the context of the novel, which describes passion in terms that seem inspired by physics as often as by poetry, “flung out of space” can be read audaciously and broadly. “Flung out of space” is what the furious little train wants to be, freed from the track that holds it hostage. “Flung out of space” is what happens to Therese’s first photographs of Carol, rendered in the fleeting, invisible instant of the shutter-click, and never to be seen in printed form. And, finally, “flung out of space” is where the film leaves us, propelled by its affective movements into uncharted territory, arcing on and on in space and time, away from the long, straight tracks laid down by the conventional romantic melodrama.

This is an expanded version of a paper published in The Cine-Files Vo. 5. I am grateful to the editors of The Cine-Files for the kind permission to use this material here.

Barker, Jennifer M. Click. Affect and Mediated Gestures in CAROL, edited by Anne Rutherford. The Cine-Files 5/10 (2016). http://www.thecine-files.com/barker2016/.

Bibliography

Ahnert, Laurel: Love, Touch and the Documentary Project. Atlanta 2017.

Allen, Jeremy: Everyone Will Be Talking About the Cars and Clothes of CAROL (2015). In: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/photo-essays/2015-11-18/the-cars-and-clothes-of-carol-todd-haynes-s-1950s-masterpiece/ [accessed 07 September 2017].

Astruc, Alexandre: What is mise en scène? In: Jim Hillier (ed.): Cahiers du Cinéma. The 1950s. Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave. Cambridge 1985, 266–268.

Barker, Jennifer M.: Be-Hold. Touch, Temporality, and the Cinematic Thumbnail Image. Discourse 35/2 (2014), 194–211.

Cochrane, Kristin: Todd Haynes’ CAROL Is the Story of a Flâneuse Who Gazes Back. Slutever (2016). In: http://slutever.com/todd-haynes-carol-queer-gaze/ [accessed 07 September 2017].

Flusser, Vilém: Gestures. Minneapolis 2014.

Fry, Naomi: Surface Matters. Todd Haynes’s CAROL mistakes aesthetics for meaning. New Republic (2015). In: https://newrepublic.com/article/123221/todd-hayness-carol-mistakes-aesthetics-meaning/ [accessed 07 September 2017].

Goldberg, Jonathan: Melodrama. An Aesthetics of Impossibility. Durham 2016.

Halliday, Jon: Sirk on Sirk. Conversations with Jon Halliday. London / Boston 1997.

Haynes, Todd: Three Screenplays. An Introduction. In: Far from Heaven, Safe, and Superstar. The Karen Carpenter Story. Three Screenplays. New York 2003, VII–XII.

Highsmith, Patricia: The Price of Salt. Mineola 2015.

Hornaday, Ann: Review. Todd Haynes’s CAROL Casts a Beguiling Spell. The Washington Post (2015). In: https://www.washingtonpost.com/goingoutguide/movies/movie-review-todd-hayness-carol-casts-a-beguiling-spell/2015/12/23/5eedbf9c-a5cf-11e5-b53d-972e2751f433_story.html?utm_term=.fb2ea6eee8c8 [accessed 07 September 2017].

Kappelhoff, Hermann / Müller, Cornelia: Embodied Meaning Construction. Multimodal Metaphor and Expressive Movement in Speech, Gesture, and Feature Film. Metaphor and the Social World 1/2 (2011), 121–153.

Martin, Adrian: A Theory of Agitation, or, Getting Off in the Cinema. Continuum 26/4 (2012), 519–528.

Martin, Adrian: Mise en Scène and Film Style. From Classical Hollywood to New Media Art. Basingstoke 2014.

Mulvey, Laura: Cinematic Gesture. The Ghost in the Machine. Journal for Cultural Research 19/1 (2015), 6–14.

Nancy, Jean-Luc: The Ground of the Image. New York 2005.

Pride, Ray: Trains, Perfume and Allure. Talking to Todd Haynes about the Swoon of CAROL. Newcity Film (2015). In: http://newcityfilm.com/2015/12/24/trains-perfume-and-allure-talking-to-todd-haynes-about-the-swoon-of-carol/ [accessed 07 September 2017].

del Río, Elena: Deleuze and the Cinemas of Performance. Powers of Affection. Edinburgh 2009.

Rosman, Lisa: The Courage of Intimacy. Todd Haynes’s CAROL Review. Signature Reads (2015). In: http://www.signature-reads.com/2015/11/the-courage-intimacy-todd-hayness-carol-review/ [accessed 07 September 2017].

Rutherford, Anne: Precarious Boundaries. Affect, Mise en scène, and the Senses in Angelopoulos’ Balkans Epic. Senses of Cinema 31 (2004). In: http://sensesofcinema.com/2004/feature-articles/angelopoulos_balkan_epic/ [accessed 07 September 2017].

Rutherford, Anne: Teaching Film and Mise en Scène. In: Lucy Fischer, Patrice Petro (eds.): Teaching Film. New York 2012, 299–310.

Schreiber, Michele: American Postfeminist Cinema. Women, Romance and Contemporary Culture. Edinburgh 2014.

Scott, A. O.: Review. CAROL Explores the Sweet Science of Magnetism. The New York Times (2015). In: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/20/movies/review-carol-explores-the-sweet-science-of-magnetism.html [accessed 07 September 2017].

Stasukevich, Iain: CAROL. American Cinematographer. The International Journal of Motion Imaging 96/12 (2015). In: https://theasc.com/ac_magazine/December2015/Carol/page1.html [accessed 07 September 2017].

Stimson, Blake: Gesture and Abstraction. In: Carrie Noland, Sally Ann Ness (eds.): Migrations of Gesture. Minneapolis 2008, 69–83.

White, Patricia: Sketchy Lesbians. CAROL as History and Fantasy. Film Quarterly 69/2 (2015), 8–18.

Filmography

BRIEF ENCOUNTER. David Lean. GB 1945.

CAROL. Todd Haynes. USA 2015.

IMITATION OF LIFE. Douglas Sirk. USA 1959.

LETTER FROM AN UNKOWN WOMAN. Max Ophüls. USA 1948.

NORTH BY NORTHWEST. Alfred Hitchcock. USA 1959.

THE LADY EVE. Preston Sturges. USA 1941.

TWENTIETH CENTURY. Howard Hawks. USA 1934.