Danny Gronmaier

- 1. Nostalgia for Pure Pasts and the Problem of Agency

- 2. The Horror of the Voice

- 3. A Future Vision of the Past

- 4. Between Strangeness and Intimacy – A First Encounter as Western Duel

- 5. The Personal is Public: A PTA Meeting as (Comic) Courtroom Drama

- 6. Time-travelling in Film History

- 7. Encountering Genre Film as Time Crystal: The Deep Temporality of the Poiesis of Film-viewing

- 8. A Community of Spectators of and as the Myth of America

- 9. History as a Process of Exclusion and a Filmic Experience of Deep Temporality

- Bibliography

- Filmography

In what follows, I want to delve deeper into the images and sounds of the FIELD OF DREAMS to propose that its “hyperbolic nostalgia”(Sobchack 1997, 179) is more reflexive than we might expect. First of all, because the film’s audiovisual poetics—by means of recreating (modulating, mixing, confronting, relating) a variety of Hollywood genre modalities—seems to aim at a genre experience that very much ponders the impurity of history, or the impossibility of purity with regard to historical experience. And second, because it thereby makes palpable how history, of which media representations are a vital part, is never innocent, never can be, as it is always the product of an address and orientation towards both specific and ever-changing senses of community—and thus, inextricably connected to constant processes of in- and exclusion.(1)

(1) Hermann Kappelhoff makes this connection between the referencing of different genre modalities of aesthetic experience and the dynamics of political pluralism evident by employing Rorty’s notion of the sense of community “as a dynamic element of a society […], which must always configure itself anew as a community”, and as a product of “the affective agreement to commonly shared values in concrete cultural practices” (Kappelhoff 2016), as well as Arendt’s reading of Kant’s aesthetic judgement of taste as an “extra sense […] that inserts us into a community” (Arendt 1992, 70, as cited in Kappelhoff 2016).

1. Nostalgia for Pure Pasts and the Problem of Agency

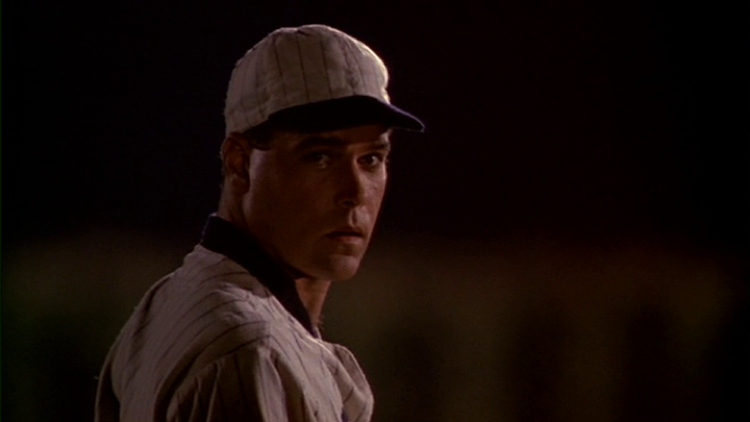

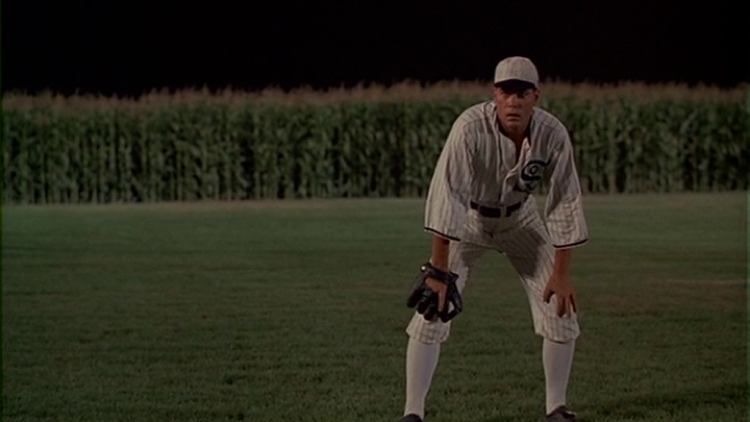

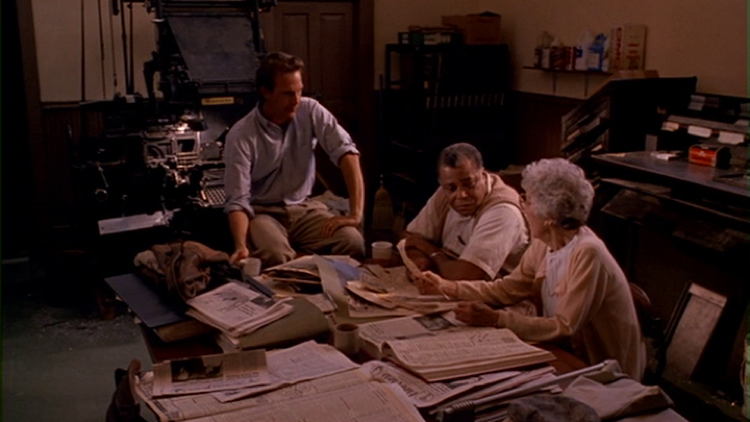

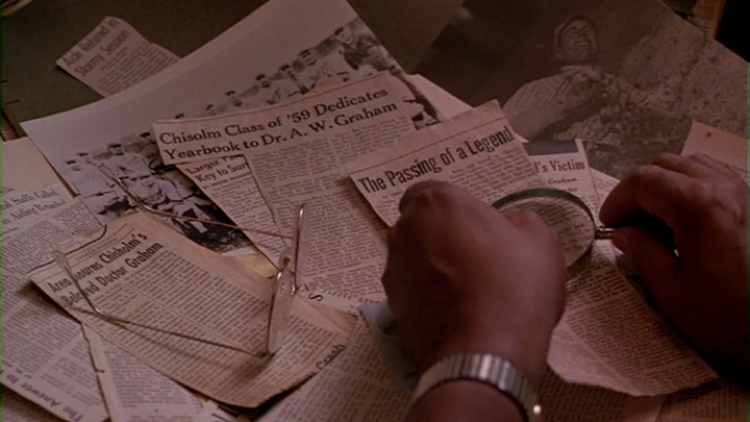

What is striking about FIELD OF DREAMS is the almost complete absence of professional game, in the sense that league games are played or watched. Rather than being or becoming a player or coach, main protagonist Ray Kinsella (Kevin Costner) is first and foremost a fan, not directly involved in athletic competition. He is, instead, a layperson commissioned to set out on an enigmatic quest: to build a ballpark for the return of (the ghost of) ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson (Ray Liotta), the most famous player involved in the so-called Black Sox Scandal in 1919, in which the Chicago White Sox conspired to fix the World Series;(2) and, moreover, to search for his and his wife Annie’s (Amy Madigan) favorite writer and former African American civil rights activist Terence Mann (James Earl Jones), as well as former player Archie ‘Moonlight’ Graham (played by Burt Lancaster and, for his younger version, by Frank Whaley).

(2) In the course of the Black Sox Scandal, eight players were accused of intentionally losing, acquitted in public trial but then nonetheless permanently banned for life from professional baseball. The incident has also been the subject of another movie, which came out only one year before FIELD OF DREAMS: While Robinson’s film uses the scandal as a kind of trigger to spark its fantasy story of belated redemption, EIGHT MEN OUT (J. Sayles, 1988) presents a multi-character narrative, which results in “a lengthy trail of constant exposition, with any real sense of the characters or their dilemma sacrificed to the unfolding plot” (Jenkins 1989, 205). For a nonfiction literary reconstruction of the scandal, see also Asinof 1963.